Business

Governor Ambode permanently bans VIO in Lagos

The Lagos State Governor, Akinwunmi Ambode, on Tuesday put to rest the uncertainty concerning the absence of Vehicle Inspection Officers, VIO, on Lagos roads, stating categorically that he has asked them to stay off the roads permanently.

Governor Ambode, who said this at the commissioning of Pedestrian Bridges, Laybys and Slip Road at Ojodu Berger, also urged the Federal Road Safety Corps, FRSC, to limit its operations to the fringes and highways and stay clear from the main streets of the state.

He said the decisions were in line with his administration’s resolve to ensure free flow of traffic across Lagos, noting that their activities were contributing to traffic congestion on Lagos roads.

“Distinguished ladies and gentlemen, let me use this opportunity to reiterate that Vehicle Inspection Officers (VIO) have been asked to stay off our roads permanently,” Mr. Ambode began at the event.

“We also advice the Federal Road Safety Corps to stay on the fringes and highways and not on the main streets of Lagos. It has become evident that these agencies contribute to the traffic challenges on our roads.”

He said as an alternative, the state government would employ technology to track and monitor vehicle registration and MOT certifications and de-emphasise impoundment of vehicles on the roads.

Speaking on the interventions in Ojodu Berger, Governor Ambode said his administration at inception, identified the axis as one of the major traffic flashpoints that required urgent attention, adding that the decision was informed by the strategic importance of this axis being a major gateway into the state.

“What we set out to achieve with this project was to ensure smooth flow of traffic along the express, safeguard the lives of our people who had to run across the express and project the image of a truly global city to our visitors.

“Today, we are delighted that we have not only succeeded in transforming the landscape of this axis but with the slip road, lay bys and pedestrian bridge, we have given a new and pleasant experience to all entering and exiting our State.

“This project is the product of our innovative team of engineers, architects and town planners who have worked hard to create an innovative solution to tackle the challenges of this axis. I say a big thank you to the staff of the Lagos State Ministry of Works and the contractors – CCECC Nigeria Limited for a job well done,” he said.

To improve on the project, Mr. Ambode said a food court would be built where people can relax before climbing the pedestrian bridge, as well as an interstate bus terminal within the Ojodu Berger axis for buses coming from outside Lagos to drop and load passengers, while intercity transportation system would move commuters within the city.

The governor also assured that his traffic interventions would not only stop at the Ojodu Berger axis, but would be an ongoing process to create solutions to traffic congestion in every part of the state.

“If your neighbourhood or community is experiencing traffic challenges, be rest assured that we will soon be there. We will always ensure that promises made are promises kept. We will continue to rely on the support of all segments of the population for regular tax payments, obeying the rule of law and protection of public infrastructure. That is the only way we can progress and achieve our goal of being one of the world’s top centres for business, entertainment and leisure,” he said.

While alluding to the fact that the state has lived up to its reputation as a land of possibilities, Mr. Ambode also expressed confidence that the future prospects of the state was promising and that the journey of the next fifty years has commenced on a very sound and solid footing.

Earlier, in his opening remarks, the state’s Commissioner for Waterfront Infrastructure Development, Adebowale Akinsanya, said the project was conceived by the state government as a response to the yearnings of the people of Ojodu Berger Community for an improved, efficient and grid lock free road network, as well as the need to preserve the sanctity of life of Lagosians who hitherto were endangered by the need to cross the ever-busy Lagos-Ibadan Expressway.

Mr. Akinsanya, who is also overseeing the Ministry of Works and Infrastructure, gave the scope of the project to include 98 metres pedestrian bridges with illumination, 150m length lay-bys on both sides of the expressway, 500m length of retaining wall with varying height from 3.5m to 7m and two multi-by bus park/bus lay-bys on Ogunnusi road with public convenience.

Other scope of the project included 650m slip road connecting traffic outward the expressway to Omole/Olowora Junction, 700m Ogunnusi/Wakatiadura dual road from Kosoko road junction to the expressway, 250m PWC Road to the expressway, street lighting on all the roads and multi-bay bus parks, signalisation of all junctions, pedestrian walkway and drainage infrastructure, among others.

Business

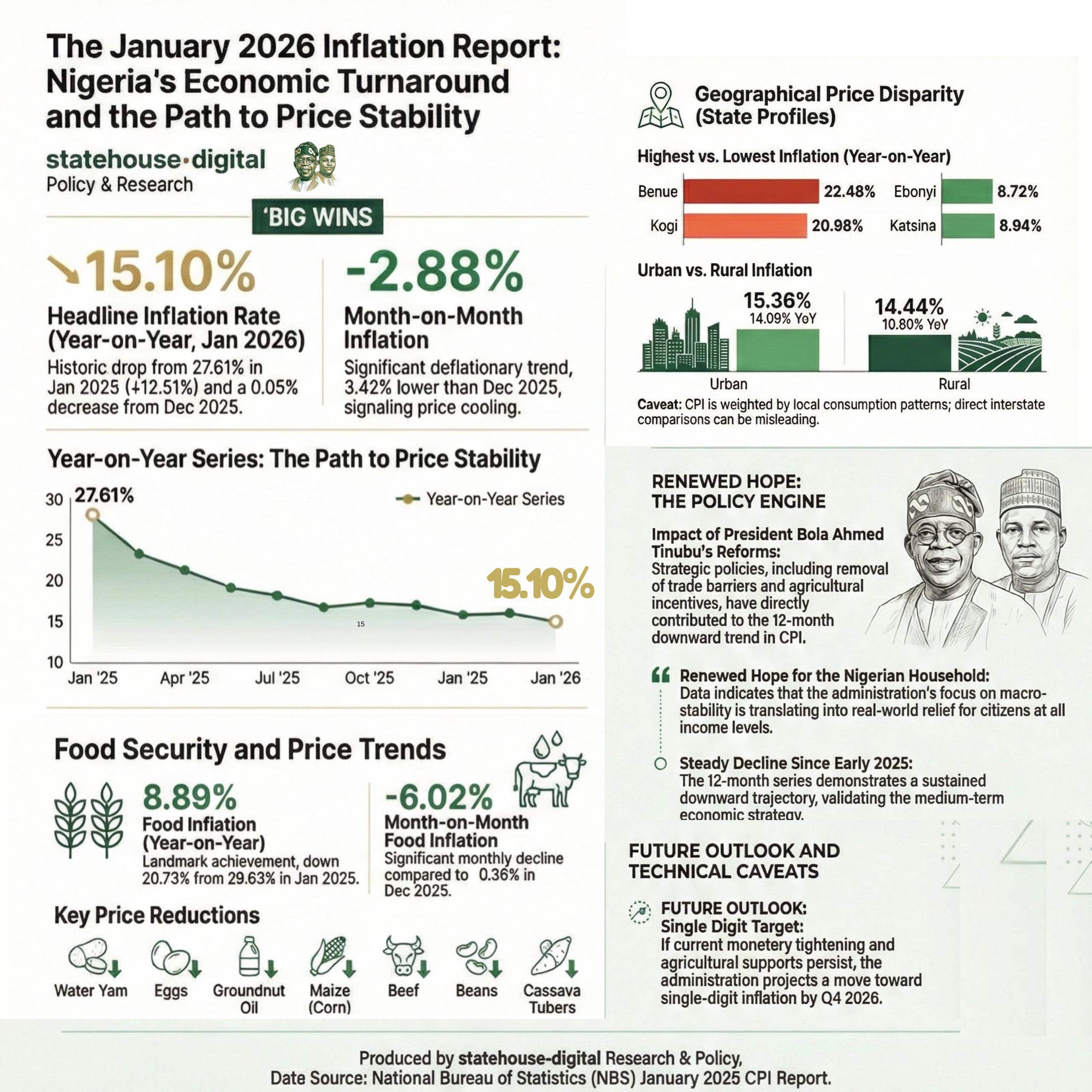

Nigeria’s Inflation Drops to 15.10% as NBS Reports Deflationary Trend

Nigeria’s headline inflation rate declined to 15.10 per cent in January 2026, marking a significant drop from 27.61 per cent recorded in January 2025, according to the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) report released by the National Bureau of Statistics.

The report also showed that month-on-month inflation recorded a deflationary trend of –2.88 per cent, representing a 3.42 percentage-point decrease compared to December 2025. Analysts say the development signals easing price pressures across key sectors of the economy.

Food inflation stood at 8.89 per cent year-on-year, down from 29.63 per cent in January 2025. On a month-on-month basis, food prices declined by 6.02 per cent, reflecting lower costs in several staple commodities.

The data suggests a sustained downward trajectory in inflation over the past 12 months, pointing to improving macroeconomic stability.

The administration of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has consistently attributed recent economic adjustments to ongoing fiscal and monetary reforms aimed at stabilising prices, boosting agricultural output, and strengthening domestic supply chains.

Economic analysts note that while the latest figures indicate progress, sustaining the downward trend will depend on continued policy discipline, exchange rate stability, and improvements in food production and distribution.

The January report provides one of the clearest indications yet that inflationary pressures, which surged in early 2025, may be moderating.

Bank

Alpha Morgan to Host 19th Economic Review Webinar

Alpha Morgan to Host 19th Economic Review Webinar

In an economy shaped by constant shifts, the edge often belongs to those with the right information.

On Wednesday, February 25, 2026, Alpha Morgan Bank will host the 19th edition of its Economic Review Webinar, a high-level thought leadership session designed to equip businesses, investors, and individuals with timely financial and economic insight.

The session, which will hold live on Zoom at 10:00am WAT and will feature economist Bismarck Rewane, who will examine the key signals influencing Nigeria’s economic direction in 2026, including policy trends, market movements, and global developments shaping the local landscape.

With a consistent track record of delivering clarity in uncertain times, the Alpha Morgan Economic Review continues to provide practical context for decision-making in a dynamic environment.

Registration for the 19th Alpha Morgan Economic Review is free and can be completed via https://bit.ly/registeramerseries19

It is a bi-monthly platform that is open to the public and is held virtually.

Visit www.alphamorganbank to know more.

Business

GTBank Launches Quick Airtime Loan at 2.95%

GTBank Launches Quick Airtime Loan at 2.95%

Guaranty Trust Bank Ltd (GTBank), the flagship banking franchise of GTCO Plc, Africa’s leading financial services group, today announced the launch of Quick Airtime Loan, an innovative digital solution that gives customers instant access to airtime when they run out of call credit and have limited funds in their bank accounts, ensuring customers can stay connected when it matters most.

In today’s always-on world, running out of airtime is more than a minor inconvenience. It can mean missed opportunities, disrupted plans, and lost connections, often at the very moment when funds are tight, and options are limited. Quick Airtime Loan was created to solve this problem, offering customers instant access to airtime on credit, directly from their bank. With Quick Airtime Loan, eligible GTBank customers can access from ₦100 and up to ₦10,000 by dialing *737*90#. Available across all major mobile networks in Nigeria, the service will soon expand to include data loans, further strengthening its proposition as a reliable on-demand platform.

For years, the airtime credit market has been dominated by Telcos, where charges for this service are at 15%. GTBank is now changing the narrative by offering a customer-centric, bank-led digital alternative priced at 2.95%. Built on transparency, convenience and affordability, Quick Airtime Loan has the potential to broaden access to airtime, deliver meaningful cost savings for millions of Nigerians, and redefine how financial services show up in everyday life, not just in banking moments.

Commenting on the product launch, Miriam Olusanya, Managing Director of Guaranty Trust Bank Ltd, said: “Quick Airtime Loan reflects GTBank’s continued focus on delivering digital solutions that are relevant, accessible, and built around real customer needs. The solution underscores the power of a connected financial ecosystem, combining GTBank’s digital reach and lending expertise with the capabilities of HabariPay to deliver a smooth, end-to-end experience. By leveraging unique strengths across the Group, we are able to accelerate innovation, strengthen execution, and deliver a more integrated customer experience across all our service channels.”

Importantly, Quick Airtime Loan highlights GTCO’s evolution as a fully diversified financial services group. Leveraging HabariPay’s Squad, the solution reinforces the Group’s ecosystem proposition by bringing together banking, payment technology, and digital channels to deliver intuitive, one-stop experiences for customers.

With this new product launch, Guaranty Trust Bank is extending its legacy of pioneering digital-first solutions that have redefined customer access to financial services across the industry, building on the proven strength of its widely adopted QuickCredit offering and the convenience of the Bank’s iconic *737# USSD Banking platform.

About Guaranty Trust Bank

Guaranty Trust Bank (GTBank) is the flagship banking franchise of GTCO Plc, a leading financial services group with a strong presence across Africa and the United Kingdom. The Bank is widely recognized for its leadership in digital banking, customer experience, and innovative financial solutions that deliver value to individuals, businesses, and communities.

About HabariPay

HabariPay is the payments fintech subsidiary of GTCO Plc, focused on enabling fast, secure, and accessible digital payments for individuals and businesses. By integrating payments and digital technology, HabariPay supports innovative services that make everyday financial interactions simpler and more seamless.

Enquiries:

GTCO

Group Corporate Communication

[email protected]

+234-1-2715227

www.gtcoplc.com

-

celebrity radar - gossips6 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips6 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

society5 months ago

society5 months agoReligion: Africa’s Oldest Weapon of Enslavement and the Forgotten Truth

-

news6 months ago

news6 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING

You must be logged in to post a comment Login