Business

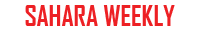

The Izuogu Z-600: Africa’s Lost Automotive Revolution

The Izuogu Z-600: Africa’s Lost Automotive Revolution.

By George Omagbemi Sylvester

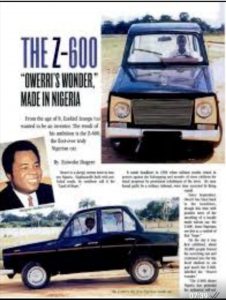

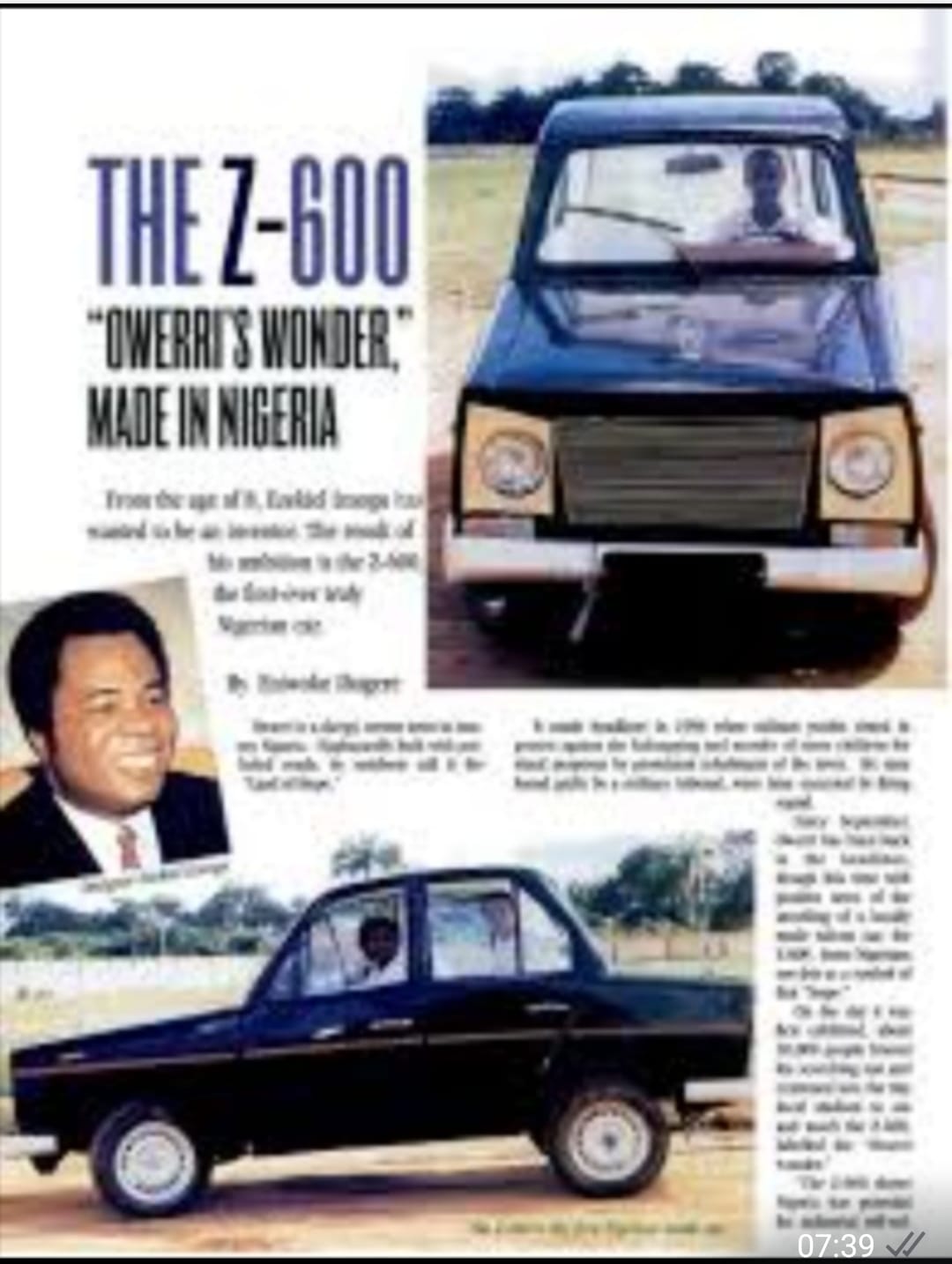

In 1997, a remarkable feat of African innovation unfolded in the heart of Imo State, Nigeria. Dr. Ezekiel Izuogu, a brilliant electrical engineer and senior lecturer at the Federal Polytechnic Nekede, unveiled what would become Africa’s first indigenous automobile: the Izuogu Z-600. It was more than a car, it was a symbol of African ingenuity, resilience and ambition. Aptly described by the BBC as the “African dream machine” the Z-600 was designed with 90% of its parts sourced locally. Its estimated retail price of just $2,000 had the potential to revolutionize transportation and economic empowerment across the continent.

A Vision Beyond Engineering

Dr. Izuogu’s dream went beyond building a car. His vision was to catalyze an industrial revolution in Nigeria, particularly in Igboland. The Z-600 was equipped with a self-made 1.8L four-cylinder engine, delivering 18 miles per gallon and reaching top speeds of 140 km/h. Front-wheel drive (FWD) was selected over rear-wheel drive (RWD) to reduce production costs, demonstrating a keen understanding of localized engineering solutions. The car was a marvel not just of machinery, but of determination in the face of overwhelming odds.

According to Dr. Izuogu, “If this car gets to mass production, Nigeria and Africa will no longer be the dumping ground for foreign cars.”

Initial Government Support and the Abandonment

Recognizing the car’s potential, the late General Sani Abacha’s administration constituted a 12-member panel of engineering experts to assess the Z-600’s roadworthiness. The committee gave the car a clean bill of health, recommending only minor cosmetic refinements. At the high-profile unveiling attended by over 20 foreign diplomats, the Nigerian government, represented by General Oladipo Diya, pledged a ₦235 million grant to support mass production.

However, like many well-meaning promises in Nigerian politics, this pledge remained unfulfilled. Not a single naira was released to Dr. Izuogu. Despite having passed official assessments and earning international interest, the Z-600 project was left to languish.

Dr. Izuogu lamented, “This was an opportunity for Nigeria to rise industrially, but it was squandered.”

Economic and Technological Loss

In 2006, a tragedy that seemed almost conspiratorial struck the Izuogu Motors factory in Naze, Imo State. At about 2:00 a.m. on March 11, twelve armed men invaded the facility, making away with vital components: the design history notebook, the Z-MASS design file for mass production, engine molds, crankshafts, pistons, camshafts and flywheels. Over ten years of research and development, worth over ₦1 billion, was effectively erased overnight.

“It seems that the target of this robbery is to stop the efforts we are making to mass-produce the first ever locally made car in Africa,” Dr. Izuogu said.

This was not just a loss to a single man, but a national economic tragedy. The theft of intellectual property on such a scale is rare and the fact that no serious investigation followed speaks volumes about the apathy toward indigenous innovation.

South African Opportunity and Another Betrayal

In 2005, a glimmer of hope emerged. The South African government, after seeing presentations of the Z-600, invited Dr. Izuogu to pitch the vehicle to a panel of top engineers. Enthralled by the innovation, South Africa offered to help set up a plant for mass production. Though flattered, Dr. Izuogu hesitated. His dream was for Nigeria to be the birthplace of an African industrial revolution not merely an exporter of talent.

Nevertheless, facing continuous neglect at home, he reluctantly began exploring the opportunity. Sadly, the robbery of 2006 dealt a final blow to this dream.

The Broader African Context

The story of the Z-600 is emblematic of a broader African malaise: the systemic failure to support indigenous innovation. According to Dr. Peter Eneh, a development economist, “Africa’s greatest tragedy is not poverty but the consistent sabotage of local ideas and talents by political inertia.”

In India, the Tata Nano was developed and rolled out in 2008, five years after Nigeria had the opportunity to lead the cheap car revolution. While the Indian government supported Tata Group with infrastructure and policy backing, Nigeria allowed politics and indifference to kill its golden goose.

As Prof. Ndubuisi Ekekwe, founder of the African Institution of Technology, noted, “Innovation dies not from lack of talent in Africa, but from institutional hostility.”

Lessons for Africa

The Izuogu Z-600 should be taught in engineering schools and policymaking institutions across Africa. It is a case study in potential wasted due to governance failure, insecurity and lack of strategic investment. The car could have generated thousands of jobs, stimulated related industries and positioned Nigeria as a pioneer in low-cost automobile manufacturing.

Instead, we mourn a lost opportunity. Dr. Izuogu’s death in 2020 closed the chapter on what might have been Africa’s most transformative technological breakthrough.

Lessons from a Forgotten Dream

Africa must learn from this colossal failure, innovation must be protected. Talent must be supported. Local entrepreneurs must be seen as national assets not nuisances.

Dr. Izuogu once said, “Our problem is not brains; our problem is the environment.” That statement still rings painfully true today.

The Tragedy of Unfulfilled Innovation

The Z-600 was not just a car but a movement, it was hope and proof that Africans can dream, design and deliver; but then dreams need nurturing. Ideas need investment. Hope needs a system that works.

Let the Z-600 remind us that the future is not given, it is made. And Africa, despite its challenges, still holds the power to create.

As the Nigerian-American businesswoman Ndidi Nwuneli puts it, “If Africa is to rise, it must learn to trust and invest in its own people.”

Let us never again allow another Z-600 to die.

Business

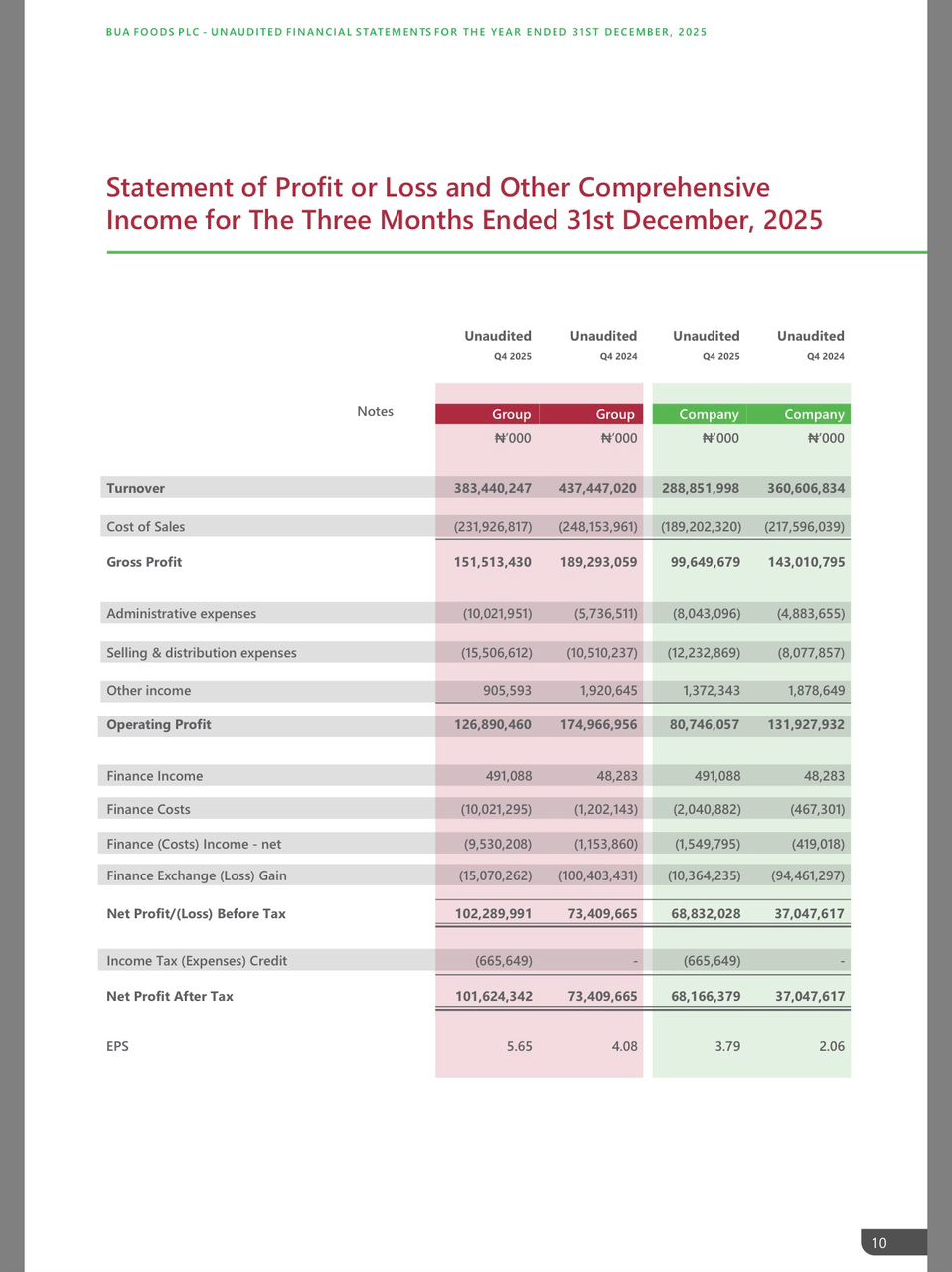

BUA Foods Records 91% Surge in Profit After Tax, Hits ₦508bn in 2025

BUA Foods Records 91% Surge in Profit After Tax, Hits ₦508bn in 2025

By femi Oyewale

Business

Adron Homes Unveils “Love for Love” Valentine Promo with Exciting Discounts, Luxury Gifts, and Travel Rewards

Adron Homes Unveils “Love for Love” Valentine Promo with Exciting Discounts, Luxury Gifts, and Travel Rewards

In celebration of the season of love, Adron Homes and Properties has announced the launch of its special Valentine campaign, “Love for Love” Promo, a customer-centric initiative designed to reward Nigerians who choose to express love through smart, lasting real estate investments.

The Love for Love Promo offers clients attractive discounts, flexible payment options, and an array of exclusive gift items, reinforcing Adron Homes’ commitment to making property ownership both rewarding and accessible. The campaign runs throughout the Valentine season and applies to the company’s wide portfolio of estates and housing projects strategically located across Nigeria.

Speaking on the promo, the company’s Managing Director, Mrs Adenike Ajobo, stated that the initiative is aimed at encouraging individuals and families to move beyond conventional Valentine gifts by investing in assets that secure their future. According to the company, love is best demonstrated through stability, legacy, and long-term value—principles that real estate ownership represents.

Under the promo structure, clients who make a payment of ₦100,000 receive cake, chocolates, and a bottle of wine, while those who pay ₦200,000 are rewarded with a Love Hamper. Payments of ₦500,000 attract a Love Hamper plus cake, and clients who pay ₦1,000,000 enjoy a choice of a Samsung phone or a Love Hamper with cake.

The rewards become increasingly premium as commitment grows. Clients who pay ₦5,000,000 receive either an iPad or an all-expenses-paid romantic getaway for a couple at one of Nigeria’s finest hotels, which includes two nights’ accommodation, special treats, and a Love Hamper. A payment of ₦10,000,000 comes with a choice of a Samsung Z Fold 7, three nights at a top-tier resort in Nigeria, or a full solar power installation.

For high-value investors, the Love for Love Promo delivers exceptional lifestyle experiences. Clients who pay ₦30,000,000 on land are rewarded with a three-night couple’s trip to Doha, Qatar, or South Africa, while purchasers of any Adron Homes house valued at ₦50,000,000 receive a double-door refrigerator.

The promo covers Adron Homes’ estates located in Lagos, Shimawa, Sagamu, Atan–Ota, Papalanto, Abeokuta, Ibadan, Osun, Ekiti, Abuja, Nasarawa, and Niger States, offering clients the opportunity to invest in fast-growing, strategically positioned communities nationwide.

Adron Homes reiterated that beyond the incentives, the campaign underscores the company’s strong reputation for secure land titles, affordable pricing, strategic locations, and a proven legacy in real estate development.

As Valentine’s Day approaches, Adron Homes encourages Nigerians at home and in the diaspora to take advantage of the Love for Love Promo to enjoy exceptional value, exclusive rewards, and the opportunity to build a future rooted in love, security, and prosperity.

Business

Why Nigeria’s Banks Still on Shaky Ground with Big Profits, Weak Capital

*Why Nigeria’s Banks Still on Shaky Ground with Big Profits, Weak Capital*

*BY BLAISE UDUNZE*

Despite the fragile 2024 economy grappling with inflation, currency volatility, and weak growth, Nigeria’s banking industry was widely portrayed as successful and strong amid triumphal headlines. The figures appeared to signal strength, resilience, and superior management as the Tier-1 banks such as Access Bank, Zenith Bank, GTBank, UBA, and First Bank of Nigeria, collectively reported profits approaching, and in some cases exceeding, N1 trillion. Surprisingly, a year later, these same banks touted as sound and solid are locked in a frenetic race to the capital markets, issuing rights offers and public placements back-to-back to meet the Central Bank of Nigeria’s N500 billion recapitalisation thresholds.

The contradiction is glaring. If Nigeria’s biggest banks are so profitable, why are they unable to internally fund their new capital requirements? Why have no fewer than 27 banks tapped the capital market in quick succession despite repeated assurances of balance-sheet robustness? And more fundamentally, what do these record profits actually say about the real health of the banking system?

The recapitalisation directive announced by the CBN in 2024 was ambitious by design. Banks with international licences were required to raise minimum capital to N500 billion by March 2026, while national and regional banks faced lower but still substantial thresholds ranging from N200 billion to N50 billion, respectively. Looking at the policy, it was sold as a modern reform meant to make banks stronger, more resilient in tough times, and better able to support major long-term economic development. In theory, strong banks should welcome such reforms. In practice, the scramble that followed has exposed uncomfortable truths about the structure of bank profitability in Nigeria.

At the heart of the inconsistency is a fundamental misunderstanding often encouraged by the banks themselves between profits and capital. Unknown to many, profitability, no matter how impressive, does not automatically translate into regulatory capital. Primarily, the CBN’s recapitalisation framework actually focuses on money paid in by shareholders when buying shares, fresh equity injected by investors over retained earnings or profits that exist mainly on paper.

This distinction matters because much of the profit surge recorded in 2024 and early 2025 was neither cash-generative nor sustainably repeatable. A significant portion of those headline banks’ profits reported actually came from foreign exchange revaluation gains following the sharp fall of the naira after exchange-rate unification. The industry witnessed that banks’ holding dollar-denominated assets their books showed bigger numbers as their balance sheets swell in naira terms, creating enormous paper profits without a corresponding improvement in underlying operational strength. These gains inflated income statements but did little to strengthen core capital, especially after the CBN barred banks from using FX revaluation gains for dividends or routine operations. In effect, banks looked richer without becoming stronger.

Beyond FX effects, Nigerian banks have increasingly relied on non-interest income fees, charges, and transaction levies to drive profitability. While this model is lucrative, it does not necessarily deepen financial intermediation or expand productive lending. High profits built on customer charges rather than loan growth offer limited support for long-term balance-sheet expansion. They also leave banks vulnerable when macroeconomic conditions shift, as is now happening.

Indeed, the recapitalisation exercise coincides with a turning point in the monetary cycle. The extraordinary conditions that supported bank earnings in 2024 and 2025 are beginning to unwind. Analysts now warn that Nigerian banks are approaching earnings reset, as net interest margins the backbone of traditional banking profitability, come under sustained pressure.

Renaissance Capital, in a January note, projects that major banks including Zenith, GTCO, Access Holdings, and UBA will struggle to deliver earnings growth in 2026 comparable to recent performance.

In a real sense, the CBN is expected to lower interest rates by 400 to 500 basis points because inflation is slowing down, and this means that banks will earn less on loans and government bonds, but they may not be able to quickly lower the interest they pay on deposits or other debts. The cash reserve requirements are still elevated, which does not earn interest; banks can’t easily increase or expand lending investments to make up for lower returns. The implications are significant. Net interest margin, the difference between what banks earn on loans and investments and what they pay on deposits, is poised to contract. Deposit competition is intensifying as lenders fight to shore up liquidity ahead of recapitalisation deadlines, pushing up funding costs. At the same time, yields on treasury bills and bonds, long a safe and lucrative haven for banks are expected to soften in a lower-rate environment. The result is a narrowing profit cushion just as banks are being asked to carry far larger equity bases.

Compounding this challenge is the fading of FX revaluation windfalls. With the naira relatively more stable in early 2026, the non-cash gains that once flattered bank earnings have largely evaporated. What remains is the less glamorous reality of core banking operations: credit risk management, cost efficiency, and genuine loan growth in a sluggish economy. In this new environment, maintaining headline profits will be far harder, even before accounting for the dilutive impact of recapitalisation.

That dilution is another underappreciated consequence of the capital rush. Massive share issuances mean that even if banks manage to sustain absolute profit levels, earnings per share and return on equity are likely to decline. Zenith, Access, UBA, and others are dramatically increasing their share counts. The same earnings pie is now being divided among many more shareholders, making individual returns leaner than during the pre-recapitalisation boom. For investors, the optics of strong profits may soon give way to the reality of weaker per-share performance.

Yet banks have pressed ahead, not only out of regulatory necessity but also strategic calculation.

During this period of recapitalization, investors are interested in the stock market with optimism, especially about bank shares, as banks are raising fresh capital, and this makes it easier to attract investments. This has become a season for the management teams to seize the moment to raise funds at relatively attractive valuations, strengthen ownership positions, and position themselves for post-recapitalisation dominance. In several cases, major shareholders and insiders have increased their stakes, as projected in the media, signalling confidence in long-term prospects even as near-term returns face pressure.

There is also a broader structural ambition at play. Well-capitalised banks can take on larger single obligor exposures, finance infrastructure projects, expand regionally, and compete more credibly with pan-African and global peers. From this perspective, recapitalisation is not merely about compliance but about reshaping the competitive hierarchy of Nigerian banking. What will be witnessed in the industry is that those who succeed will emerge larger, fewer, and more powerful. Those that fail will be forced into consolidation, retreat, or irrelevance.

For the wider economy, the outcome is ambiguous. Stronger banks with deeper capital buffers could improve systemic stability and enhance Nigeria’s ability to fund long-term development. The point is that while merging or consolidating banks may make them safer, it can also harm the market and the economy because it will reduce competition, let a few banks dominate, and encourage them to earn easy money from bonds and fees instead of funding real businesses. The truth be told, injecting more capital into the banks without complementary reforms in credit infrastructure, risk-sharing mechanisms, and fiscal discipline, isn’t enough as the aforementioned reforms are also needed.

The rush as exposed in this period, is that the moment Nigerian banks started raising new capital, the glaring reality behind their reported profits became clearer, that profits weren’t purely from good management, while the financial industry is not as sound and strong as its headline figures. The fact that trillion-naira profit banks must return repeatedly to shareholders for fresh capital is not a sign of excess strength, but of structural imbalance.

With the deadline for banks to raise new capital coming soon, by 31 March 2026, the focus has shifted from just raising N500 billion. N200 billion or N50 billion to think about the future shape and quality of Nigeria’s financial industry, or what it will actually look like afterward. Will recapitalisation mark a turning point toward deeper intermediation, lower dependence on speculative gains, and stronger support for economic growth? Or will it simply reset the numbers while leaving underlying incentives unchanged?

The answer will define the next chapter of Nigerian banking long after the capital market roadshows have ended and the profit headlines have faded.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: [email protected]

-

celebrity radar - gossips6 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips6 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

Business6 months ago

Business6 months agoBatsumi Travel CEO Lisa Sebogodi Wins Prestigious Africa Travel 100 Women Award

-

news6 months ago

news6 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING