Business

Currency over Character: How Nigeria Rewarded Wealth and Forgot Integrity in our Today’s Society

Currency over Character: How Nigeria Rewarded Wealth and Forgot Integrity in our Today’s Society.

Written by George Omagbemi Sylvester | Published by SaharaWeeklyNG.com

In today’s Nigeria, wealth has become the defining metric of value, not INTEGRITY, not PATRIOTISM, not INNOVATION, not SERVICE to COMMUNITY. Whether in politics, social circles and in churches, Nigerians have elevated MONEY above MORALS, RICHES above RIGHTEOUSNESS and LUXURY above LEGACY. We worship the rich, regardless of how they made their wealth. We sing praises for criminals in agbada, roll out red carpets for looters and even allow drug barons and fraudsters to define the standards of success. This dangerous social erosion has triggered a national identity crisis, one where the HONEST are MOCKED and the CORRUPT are IDOLIZED. How did we get here?

A Culture of Financial Worship. From the beer parlors in Lagos to the political rallies in Kano, the most consistent measure of respect in Nigeria today is money. It does not matter how it is made, (CYBER-FRAUD, LOOTING GOVERNMENT FUNDS, DRUG-TRAFFICKING, RITUAL-KILLINGS/ BLOOD-MONEY) what matters is that you can “spray” bundles of naira in public. Once you have money, pastors give you front-row seats in churches, politicians beg for your endorsement, musicians mention your name in their songs and your sins are forgiven with a smiling face. We are now a country where “I better pass my neighbor” is not about humility or effort, but about showing off wealth that often comes from suspicious sources. The moral compass of the average Nigerian has been distorted by financial desperation and a lack of consequence for bad behavior.

The Political Arena, a Market of Madness. Nigerian politics today is not a place for statesmen, it is a jungle for the highest spender. A candidate’s manifesto is less important than the rice and cash he distributes. Votes are sold like tomatoes in the market. The electorate demands money in exchange for loyalty, and politicians, in return, loot public coffers to recover their “INVESTMENT.” It is a VICIOUS CYCLE of ROT. Take the example of the 2023 general elections. Several candidates with clear criminal pasts or poor records in governance were overwhelmingly supported because they were wealthy. Many were even celebrated as “SMART” or “SHARP” simply for outwitting the system. “Any man wey no get money for Nigeria no fit talk,” this is the reflecting sad truth; MONEY, not MORALS, is POWER. As Nigerian music icon African China bitterly sang in his early 2000s protest anthem: “Poor man wey thief maggi dem go show him face for crime fighter… but rich man wey thief money na dem dem dey call oga…” This lyric still echoes today; poor people are shamed publicly, while the rich who steal billions are praised, given national honors and even elected into public office. This double standard has become normalized in Nigerian society.

In the Social Space: Influencers over Intellectuals. Social media has made this financial worship even worse. Nigerian influencers flaunt luxury lifestyles paid for by fraud, yet they are invited to high-level events and brand endorsements. We have normalized mediocrity and elevated vanity. A PhD holder earning an honest living gets less respect than a flamboyant fraudster in designer shoes. Honest hard work is mocked and words like “LEGIT” are said with pity, “you still dey do legit work in this economy?” From slay queens sleeping with politicians to politicians looting money meant for the people, money has become the altar we sacrifice our values on. In the words of David Hundeyin, Nigerian investigative journalist/global analyst: “The fastest way to become IRRELEVANT in Nigeria is to insist on INTEGRITY. This country respects AUDACITY not HONESTY.” Hundeyin’s words are a reflection of the harsh reality that Nigerian society punishes those who play by the rules.

Diaspora Voices: Shame Abroad, Glory at Home.

Ironically, many Nigerians who are disgraced abroad for fraud or money laundering become local heroes when they return home. A Nigerian caught with drugs in Indonesia might face the death penalty, if he survives and returns, he’ll be welcomed like a king in his village. We do not care about the source; we just want to see money. Iyinoluwa Aboyeji, co-founder of Andela and Flutterwave, once warned: “If we keep choosing men with no conscience to lead us just because they have cash, our nation will keep bleeding GENIUS to other nations.” That is the tragedy. While other countries are building the future with talent, Nigeria is losing hers to a value crisis.

Why Did This Happen? Several factors contributed to this national tragedy ie,

ECONOMIC HARDSHIP: With over 63% of Nigerians living in multidimensional poverty, people have become desperate. Survival not dignity, becomes the goal. As a result, anyone who escapes poverty (legally or illegally) becomes a role model.

FAILED INSTITUTIONS: The judiciary is compromised, the police are bribable and anti-corruption agencies often act as political weapons. When institutions fail to punish bad behavior, society begins to see crime as a smart move.

BROKEN VALUE SYSTEM: Parents no longer raise children to be morally upright but to be financially successful, “my SON is abroad,” they boast, even if he is in jail. Teachers demand bribes, clerics pray for corrupt politicians and role models are now Instagram scammers and reality TV stars.

MEDIA COMPLICITY: Many Nigerian media platforms give more coverage to celebrities than scholars. They promote those who flaunt wealth and ignore those who live quietly with integrity.

RELIGIOUS HYPOCRISY: Churches and mosques now prioritize donations over discipline. A corrupt man can be made a deacon, imam or church elder if he gives enough money. Prosperity is now confused with piety.

CONSEQUENCES of REWARDING BAD BEHAVIOR &

MORAL DECAY: When society rewards fraudsters and looters, the next generation grows up thinking crime pays.

LOSS of PATRIOTISM: Honest Nigerians feel alienated and many seek to leave the country.

POLITICAL DESTRUCTION: Leaders who buy their way into power do not feel accountable to the people.

ECONOMIC DAMAGE: Fraud, corruption and embezzlement drive away investors and kill local industries.

The Way Forward: Is A Valued Rebirth. If Nigeria must survive and thrive, it must return to a value system where CHARACTER not CASH, is celebrated. Schools must teach ETHICS, not just ECONOMICS. Media houses must highlight TRUTH-TELLERS not just TRENDSETTERS. Political parties must vet candidates based on INTEGRITY not just INFLUENCE. Religious leaders must speak TRUTH-TO-POWER not BOW-TO-IT. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a celebrated Nigerian author and global voice of conscience, said: “When we abandon our principles in the pursuit of power or money, we also abandon the soul of our nation.” Adichie’s words pierce through the illusion of materialism and expose the spiritual bankruptcy that afflicts Nigerian society. We must start naming and shaming looters not hailing them. We must reward honesty even if it does not come with wealth. We must teach our children that VALUE is in VIRTUE not VANITY; and we must elect leaders who live by PRINCIPLE not PRICE-TAGS.

The Bottom Line: Nigeria is at a moral crossroads. We can either continue down this dangerous path of celebrating corruption and losing our soul as a nation or we can turn back and reclaim our values. The future of our country depends on who we choose to honor, the MAN-OF-IINTEGRITY or the MAN-OF-ILLICIT WEALTH. Let us remember the prophetic words of African China, still relevant two decades later:“Poor man wen thief maggi dem go show am for TV but Richman thief money na oga dem dey hail am”.

It is time to stop clapping for CRIMINALS. It is time to rewrite the story of Nigeria; one where CHARACTER not CASH takes the CROWN.

Written by George Omagbemi Sylvester

Published by SaharaWeeklyNG.com

Business

Adron Homes Unveils “Love for Love” Valentine Promo with Exciting Discounts, Luxury Gifts, and Travel Rewards

Adron Homes Unveils “Love for Love” Valentine Promo with Exciting Discounts, Luxury Gifts, and Travel Rewards

In celebration of the season of love, Adron Homes and Properties has announced the launch of its special Valentine campaign, “Love for Love” Promo, a customer-centric initiative designed to reward Nigerians who choose to express love through smart, lasting real estate investments.

The Love for Love Promo offers clients attractive discounts, flexible payment options, and an array of exclusive gift items, reinforcing Adron Homes’ commitment to making property ownership both rewarding and accessible. The campaign runs throughout the Valentine season and applies to the company’s wide portfolio of estates and housing projects strategically located across Nigeria.

Speaking on the promo, the company’s Managing Director, Mrs Adenike Ajobo, stated that the initiative is aimed at encouraging individuals and families to move beyond conventional Valentine gifts by investing in assets that secure their future. According to the company, love is best demonstrated through stability, legacy, and long-term value—principles that real estate ownership represents.

Under the promo structure, clients who make a payment of ₦100,000 receive cake, chocolates, and a bottle of wine, while those who pay ₦200,000 are rewarded with a Love Hamper. Payments of ₦500,000 attract a Love Hamper plus cake, and clients who pay ₦1,000,000 enjoy a choice of a Samsung phone or a Love Hamper with cake.

The rewards become increasingly premium as commitment grows. Clients who pay ₦5,000,000 receive either an iPad or an all-expenses-paid romantic getaway for a couple at one of Nigeria’s finest hotels, which includes two nights’ accommodation, special treats, and a Love Hamper. A payment of ₦10,000,000 comes with a choice of a Samsung Z Fold 7, three nights at a top-tier resort in Nigeria, or a full solar power installation.

For high-value investors, the Love for Love Promo delivers exceptional lifestyle experiences. Clients who pay ₦30,000,000 on land are rewarded with a three-night couple’s trip to Doha, Qatar, or South Africa, while purchasers of any Adron Homes house valued at ₦50,000,000 receive a double-door refrigerator.

The promo covers Adron Homes’ estates located in Lagos, Shimawa, Sagamu, Atan–Ota, Papalanto, Abeokuta, Ibadan, Osun, Ekiti, Abuja, Nasarawa, and Niger States, offering clients the opportunity to invest in fast-growing, strategically positioned communities nationwide.

Adron Homes reiterated that beyond the incentives, the campaign underscores the company’s strong reputation for secure land titles, affordable pricing, strategic locations, and a proven legacy in real estate development.

As Valentine’s Day approaches, Adron Homes encourages Nigerians at home and in the diaspora to take advantage of the Love for Love Promo to enjoy exceptional value, exclusive rewards, and the opportunity to build a future rooted in love, security, and prosperity.

Business

Why Nigeria’s Banks Still on Shaky Ground with Big Profits, Weak Capital

*Why Nigeria’s Banks Still on Shaky Ground with Big Profits, Weak Capital*

*BY BLAISE UDUNZE*

Despite the fragile 2024 economy grappling with inflation, currency volatility, and weak growth, Nigeria’s banking industry was widely portrayed as successful and strong amid triumphal headlines. The figures appeared to signal strength, resilience, and superior management as the Tier-1 banks such as Access Bank, Zenith Bank, GTBank, UBA, and First Bank of Nigeria, collectively reported profits approaching, and in some cases exceeding, N1 trillion. Surprisingly, a year later, these same banks touted as sound and solid are locked in a frenetic race to the capital markets, issuing rights offers and public placements back-to-back to meet the Central Bank of Nigeria’s N500 billion recapitalisation thresholds.

The contradiction is glaring. If Nigeria’s biggest banks are so profitable, why are they unable to internally fund their new capital requirements? Why have no fewer than 27 banks tapped the capital market in quick succession despite repeated assurances of balance-sheet robustness? And more fundamentally, what do these record profits actually say about the real health of the banking system?

The recapitalisation directive announced by the CBN in 2024 was ambitious by design. Banks with international licences were required to raise minimum capital to N500 billion by March 2026, while national and regional banks faced lower but still substantial thresholds ranging from N200 billion to N50 billion, respectively. Looking at the policy, it was sold as a modern reform meant to make banks stronger, more resilient in tough times, and better able to support major long-term economic development. In theory, strong banks should welcome such reforms. In practice, the scramble that followed has exposed uncomfortable truths about the structure of bank profitability in Nigeria.

At the heart of the inconsistency is a fundamental misunderstanding often encouraged by the banks themselves between profits and capital. Unknown to many, profitability, no matter how impressive, does not automatically translate into regulatory capital. Primarily, the CBN’s recapitalisation framework actually focuses on money paid in by shareholders when buying shares, fresh equity injected by investors over retained earnings or profits that exist mainly on paper.

This distinction matters because much of the profit surge recorded in 2024 and early 2025 was neither cash-generative nor sustainably repeatable. A significant portion of those headline banks’ profits reported actually came from foreign exchange revaluation gains following the sharp fall of the naira after exchange-rate unification. The industry witnessed that banks’ holding dollar-denominated assets their books showed bigger numbers as their balance sheets swell in naira terms, creating enormous paper profits without a corresponding improvement in underlying operational strength. These gains inflated income statements but did little to strengthen core capital, especially after the CBN barred banks from using FX revaluation gains for dividends or routine operations. In effect, banks looked richer without becoming stronger.

Beyond FX effects, Nigerian banks have increasingly relied on non-interest income fees, charges, and transaction levies to drive profitability. While this model is lucrative, it does not necessarily deepen financial intermediation or expand productive lending. High profits built on customer charges rather than loan growth offer limited support for long-term balance-sheet expansion. They also leave banks vulnerable when macroeconomic conditions shift, as is now happening.

Indeed, the recapitalisation exercise coincides with a turning point in the monetary cycle. The extraordinary conditions that supported bank earnings in 2024 and 2025 are beginning to unwind. Analysts now warn that Nigerian banks are approaching earnings reset, as net interest margins the backbone of traditional banking profitability, come under sustained pressure.

Renaissance Capital, in a January note, projects that major banks including Zenith, GTCO, Access Holdings, and UBA will struggle to deliver earnings growth in 2026 comparable to recent performance.

In a real sense, the CBN is expected to lower interest rates by 400 to 500 basis points because inflation is slowing down, and this means that banks will earn less on loans and government bonds, but they may not be able to quickly lower the interest they pay on deposits or other debts. The cash reserve requirements are still elevated, which does not earn interest; banks can’t easily increase or expand lending investments to make up for lower returns. The implications are significant. Net interest margin, the difference between what banks earn on loans and investments and what they pay on deposits, is poised to contract. Deposit competition is intensifying as lenders fight to shore up liquidity ahead of recapitalisation deadlines, pushing up funding costs. At the same time, yields on treasury bills and bonds, long a safe and lucrative haven for banks are expected to soften in a lower-rate environment. The result is a narrowing profit cushion just as banks are being asked to carry far larger equity bases.

Compounding this challenge is the fading of FX revaluation windfalls. With the naira relatively more stable in early 2026, the non-cash gains that once flattered bank earnings have largely evaporated. What remains is the less glamorous reality of core banking operations: credit risk management, cost efficiency, and genuine loan growth in a sluggish economy. In this new environment, maintaining headline profits will be far harder, even before accounting for the dilutive impact of recapitalisation.

That dilution is another underappreciated consequence of the capital rush. Massive share issuances mean that even if banks manage to sustain absolute profit levels, earnings per share and return on equity are likely to decline. Zenith, Access, UBA, and others are dramatically increasing their share counts. The same earnings pie is now being divided among many more shareholders, making individual returns leaner than during the pre-recapitalisation boom. For investors, the optics of strong profits may soon give way to the reality of weaker per-share performance.

Yet banks have pressed ahead, not only out of regulatory necessity but also strategic calculation.

During this period of recapitalization, investors are interested in the stock market with optimism, especially about bank shares, as banks are raising fresh capital, and this makes it easier to attract investments. This has become a season for the management teams to seize the moment to raise funds at relatively attractive valuations, strengthen ownership positions, and position themselves for post-recapitalisation dominance. In several cases, major shareholders and insiders have increased their stakes, as projected in the media, signalling confidence in long-term prospects even as near-term returns face pressure.

There is also a broader structural ambition at play. Well-capitalised banks can take on larger single obligor exposures, finance infrastructure projects, expand regionally, and compete more credibly with pan-African and global peers. From this perspective, recapitalisation is not merely about compliance but about reshaping the competitive hierarchy of Nigerian banking. What will be witnessed in the industry is that those who succeed will emerge larger, fewer, and more powerful. Those that fail will be forced into consolidation, retreat, or irrelevance.

For the wider economy, the outcome is ambiguous. Stronger banks with deeper capital buffers could improve systemic stability and enhance Nigeria’s ability to fund long-term development. The point is that while merging or consolidating banks may make them safer, it can also harm the market and the economy because it will reduce competition, let a few banks dominate, and encourage them to earn easy money from bonds and fees instead of funding real businesses. The truth be told, injecting more capital into the banks without complementary reforms in credit infrastructure, risk-sharing mechanisms, and fiscal discipline, isn’t enough as the aforementioned reforms are also needed.

The rush as exposed in this period, is that the moment Nigerian banks started raising new capital, the glaring reality behind their reported profits became clearer, that profits weren’t purely from good management, while the financial industry is not as sound and strong as its headline figures. The fact that trillion-naira profit banks must return repeatedly to shareholders for fresh capital is not a sign of excess strength, but of structural imbalance.

With the deadline for banks to raise new capital coming soon, by 31 March 2026, the focus has shifted from just raising N500 billion. N200 billion or N50 billion to think about the future shape and quality of Nigeria’s financial industry, or what it will actually look like afterward. Will recapitalisation mark a turning point toward deeper intermediation, lower dependence on speculative gains, and stronger support for economic growth? Or will it simply reset the numbers while leaving underlying incentives unchanged?

The answer will define the next chapter of Nigerian banking long after the capital market roadshows have ended and the profit headlines have faded.

Blaise, a journalist and PR professional, writes from Lagos and can be reached via: [email protected]

Business

Nigeria’s Golden Fiscal Hour: The 1979 Budget Surplus and What It Teaches Today

Nigeria’s Golden Fiscal Hour: The 1979 Budget Surplus and What It Teaches Today.

By George Omagbemi Sylvester | Published by SaharaWeeklyNG.com

“How Nigeria’s Brief Macroeconomic Triumph Under the Second Republic Reveals Enduring Lessons for Fiscal Responsibility.”

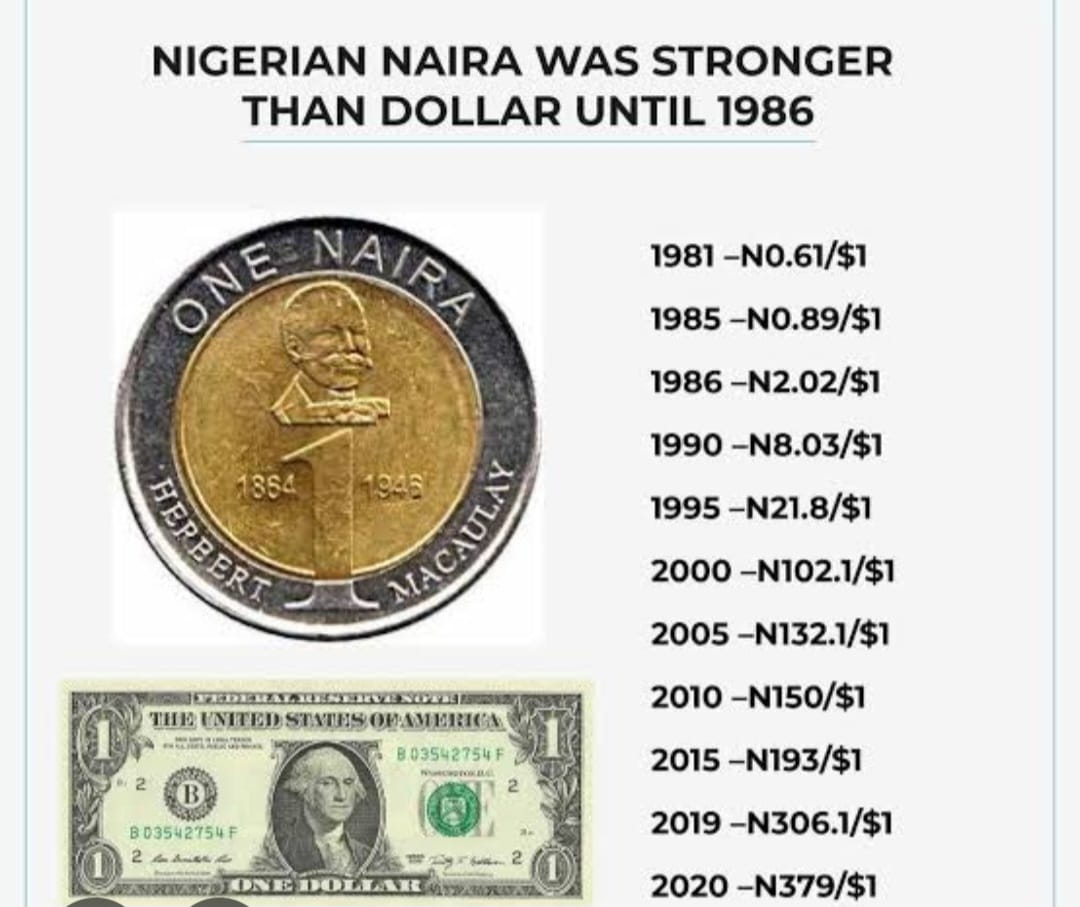

In the annals of Nigeria’s economic history, one year stands out as an extraordinary testament to fiscal prudence, macroeconomic strength, and external competitiveness: 1979. In that year, the Federal Republic of Nigeria recorded a remarkable budget surplus of approximately N1.5 billion. To fully appreciate the historical weight of this achievement, consider that the naira was stronger than the U.S. dollar at the time, trading at roughly ₦0.596 to US $1, meaning Nigeria’s surplus was equivalent to about US $2.51 billion in 1979 terms. This was not merely a statistic; it was a powerful demonstration that Nigeria could, under the right conditions, balance its books, build reserves and exercise sovereign economic judgment, lessons that remain urgently relevant today.

The Context: A Nation Riding the Oil Boom. The late 1970s were defined by an unprecedented oil windfall for Nigeria. Global oil prices surged in the wake of geopolitical shocks (notably the 1979 Iranian Revolution) which disrupted supply and drove crude prices upward. As a result, Nigeria’s oil revenues soared. Oil constituted the dominant share of the country’s export earnings, accounting for approximately 90-95% of total export earnings during this period. This influx underpinned rapid economic expansion and offered an exceptional opportunity for fiscal stability under civilian rule.

In fact, the International Monetary Fund reported that Nigeria’s foreign exchange reserves jumped from about US $1.9 billion in 1978 to an estimated US $5.5 billion in 1979, demonstrating the scale of the macroeconomic turnaround.

Yet even against the backdrop of a booming oil sector, achieving a budget surplus (where government revenues exceed expenditures) was no small feat. Most developing countries, especially those heavily reliant on volatile commodity exports, rarely achieve such fiscal discipline. For Nigeria, whose public sector had expanded dramatically in the post-civil war era, maintaining balanced books spoke to prudent revenue management during an era of extraordinary windfalls.

1979: A Snapshot of Fiscal Triumph.

1. Strong Currency –

The naira’s strength in 1979 was more than symbolic. At a time when the Nigerian currency was stronger than the dollar (a feat nearly unimaginable today) it reflected healthy foreign exchange reserves, robust export receipts and confidence in external accounts. A strong currency made imports relatively affordable and kept external liabilities manageable, though it also posed challenges for export competitiveness in non-oil sectors.

2. Budgets Balanced –

Nigeria’s budget position in 1979 stands out against a historical backdrop of chronic fiscal deficits. According to research drawing on Central Bank of Nigeria and Budget Office data, budget surplus years in Nigeria have been rare, with 1979 among only a handful of years (including 1971, 1973, 1974, 1995, and 1996) over several decades where revenues exceeded expenditures.

3. Macroeconomic Stability –

This surplus was achieved without the crippling austerity that often accompanies fiscal discipline in other contexts. Instead, it coincided with a period of economic expansion, rising domestic consumption and relative external balance. The balance of payments turned positive and foreign reserves rebounded sharply, signalling sound external-sector performance.

Leadership and Policy: The Second Republic’s Role. In October 1979, Nigeria transitioned to civilian rule with the inauguration of President Shehu Shagari and the beginning of the Second Republic (1979–1983). This political change coincided with the fiscal surplus, but it was the continuity of prudent economic management, initially grounded in the policies of the preceding military regime, that made the surplus possible.

The civilian government inherited an economy with strong export earnings and ample reserves. Instead of squandering the moment, it entered into the fiscal year with a disciplined budget anchored in realistic revenue projections. It balanced the competing demands of development and fiscal responsibility with a rare diplomatic and policy achievement in any developing economy.

As noted by respected economists studying Nigeria’s fiscal history, “budget deficits have become a norm in Nigeria’s fiscal operations since the early 1970s, with very few exceptions and 1979 being one of them.” This underscores the exceptional nature of this year.

Why the Surplus Matters for Today.

1. A Benchmark for Fiscal Responsibility.

Today’s policymakers (whether in Nigeria or comparable resource-rich developing states) would do well to study how Nigeria managed its finances in 1979. The surplus was not a result of reckless spending or short-term boom for boom’s sake; it was the product of balanced budgeting, strategic revenue retention and external competitiveness.

2. Oil Dependence Is a Double-Edged Sword.

The 1979 surplus was heavily tied to the oil boom. Critics have long warned that reliance on a single commodity exposes economies to price swings and revenue volatility. Indeed, after 1980, the global oil market underwent downturns that contributed to fiscal deficits and even economic contraction in the early 1980s. Nigeria’s experience shows that fiscal surplus driven by a volatile commodity must be paired with diversification and prudent saving.

3. Institutionalizing Discipline.

One lesson often cited by economic historians is that the absence of strong institutional frameworks for revenue management and expenditure control leads to poor outcomes once boom conditions fade. In Nigeria’s case, the later 1980s saw structural adjustment programmes, external debt accumulation, currency depreciation and social strain though all consequences of weakening fiscal discipline post-surplus era.

A respected contemporary economist once said, “Fiscal prudence is not about cutting spending at all costs; it is about strategic investment in human capital, infrastructure and savings for future volatility.” In this sense, 1979 was not just a moment of accounting success but it was also a model of strategic fiscal governance.

The Human and Institutional Dimension. While macroeconomic statistics tell one part of the story, the human and institutional dimensions are equally crucial. In 1979, Nigeria benefited from:

Strong revenue inflows, especially from crude oil

A disciplined budget office that resisted profligate spending

Coordination between the executive and legislative branches on fiscal policy

These elements helped ensure that revenues were not dissipated on unproductive expenditure or unchecked public sector expansion. Instead, the surplus created headroom for reserves and debt management strategies that strengthened Nigeria’s external accounts.

By contrast, in later decades, poor fiscal planning, unchecked borrowing and weak oversight eroded Nigeria’s fiscal capacity, contributing to perennial deficits and growing debt burdens.

Where This Leaves Nigeria: Lessons from History. The 1979 Nigerian budget surplus (N1.5 billion at a time when the naira was stronger than the dollar) represents a moment of economic possibility that transcended its era. It demonstrated that oil wealth, when managed with discipline and foresight, can yield balanced budgets, strong external positions, and macroeconomic stability. It showed that an African economy could manage its resources wisely, even under the pressures of political transition.

As Nigeria faces the complexities of the 21st-century global economy, the story of 1979 should not be a footnote, it should be a guidepost. The fiscal discipline exhibited in that year remains one of the most compelling lessons in responsible governance and strategic economic planning.

Where others see nostalgia, prudent economists see a blueprint for sustainable fiscal policy. In an era of volatile commodity markets, rising public debt, and pressure for social spending, the legacy of 1979 challenges contemporary leaders to balance aspiration with accountability.

This is not merely economic history. It is an intellectual inheritance and a reminder that competent governance, rooted in facts and disciplined budgeting, can still chart a prosperous course for Nigeria’s future.

-

celebrity radar - gossips5 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips5 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society5 months ago

society5 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

Business6 months ago

Business6 months agoBatsumi Travel CEO Lisa Sebogodi Wins Prestigious Africa Travel 100 Women Award

-

news6 months ago

news6 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING