society

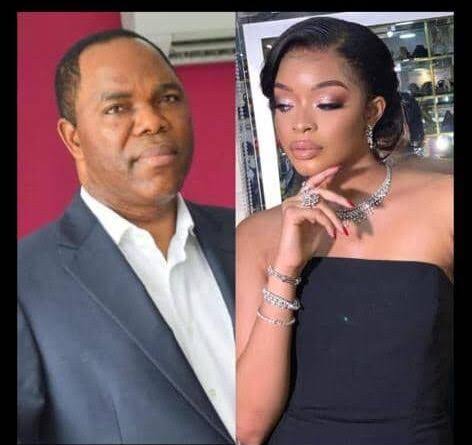

How Adaobi Alagwu and her Mother Turned Tunde Ayeni Into a Meal Ticket

*How Adaobi Alagwu and her Mother Turned Tunde Ayeni Into a Meal Ticket*

A fierce undertow runs beneath the sensational rumours of Adaobi Alagwu’s reconciliation with her estranged lover, Tunde Ayeni: it is that Ms. Alagwu and her mother, Adaora Amam, are shameless gold diggers who have turned Ayeni into their meal ticket. While Ayeni is far from blameless, the picture painted by close observers shows a calculated, deeply dependent relationship extended over years, not out of love, but out of financial survival and strategic leverage.

Sources close to the matter claim that Adaobi receives a monthly allowance from Ayeni ranging between N500,000 and N1 million, enough to underwrite much of her and her mother’s lifestyle. Even amid estrangement, she and her mother reportedly continue to occupy Ayeni’s properties: houses in Abuja, residences near his business facilities, and other assets he makes available for their use. Ayeni has become the anchor for a parasitic ecosystem, one that gladly tolerates public humiliation, controversy, even court battles, as long as the cash keeps flowing.

That ecosystem thrives on dependency. While Ayeni has publicly tried to reject or disown Adaobi even signing legal affidavits; she refuses to let go. She clings, because Ayeni remains her primary source of wealth and access, and because, despite multiple ruptures, he continues to fund her lifestyle. Her persistence goes beyond love or delusion: it looks like calculated survival.

Worse still, Adaobi has not confined her emotional life to Ayeni alone. Reports suggest that she has entertained multiple relationships with other men while still leveraging her connection to him. Such rumors, whether fully verified or not, point to a disconcerting reality: she may well treat Ayeni as the central pillar upon which she stages her social and material existence.

Her mother, according to several accounts, has played an even more troubling role: not as a protective parent, but as a strategist who both encourages and benefits from her daughter’s closeness to Ayeni. Insiders describe her as a woman who uprooted her life, abandoned her marital home, and relocated specifically to one of Ayeni’s houses at Plot 48, Mike Akhigbe Way, in Jabi, Abuja, while her daughter, Adaobi occupies Ayeni’s DD38, Lakeview Estates, off Alex Ekwueme Way, also in Abuja. For instance, Madam Adaora reportedly urged Adaobi to conceal vital truths at the beginning of her ill-fated romance with Ayeni, like her pregnancy, in a desperate bid to stretch the relationship’s limits until they could extract maximum advantage.

These findings are sharpened by commentary on a wider generational shift: wealthy older men who once wielded control in quiet, private ways now find themselves entangled with younger, digitally empowered women who understand emotional leverage, financial access, and social capital in ways their predecessors did not. The story of Ayeni, Adaobi, and her mother is not simply a private scandal. It is a dramatic confirmation of how power, money, and dependency have reconfigured contemporary relationships.

From those who know the players, Adaobi Alagwu was never cast in the role of a rescued young lover. Rather, she is portrayed as someone who recognized early that proximity to Ayeni could carry long-term benefit, and then positioned herself accordingly. Observers close to their circle say she never saw him merely as a romantic interest, but as an opportunity.

Evidence supporting this theory is public enough. Ayeni has reportedly provided her with a steady monthly stipend, and insiders claim she was still receiving those transfers even during times of public scandal. In some of his more revealing interviews, he has admitted regret, speaking of manipulation, entitlement, and emotional blackmail from Adaobi and her family.

According to those familiar with the situation, Adaobi never hesitated to dress elegantly and visit Ayeni’s office repeatedly, smiling through the awkwardness of knowing his wife was equally in Lagos. For years, whispers circulated about multiple men linked to Adaobi within their social circles, yet her mother continued to champion Ayeni as the ultimate catch. She even advised her daughter not to call him on weekends because “he would be with his wife in Lagos.”

When the secret “engagement” took place, an event without photographs at Ayeni’s insistence, the mother readily played along. Even after Ayeni questioned the child’s paternity, she would regularly show up at his office to beg. Ayeni would later remark that her requests had become routine, including asking for “One Million Naira for prayers.” And when he demanded the return of the bride price, she casually asked if it should be done formally or simply “arranged.”

Despite scolding from her husband’s kinsmen, she persisted, reportedly touring Abuja and introducing her daughter as “Mrs. Ayeni,” while simultaneously benefiting from his resources: a UK scholarship for her second daughter, and a lucrative job at NDHPC for her son. It became an ecosystem of dependence disguised as aspiration.

But money alone does not capture the full picture. According to Adaobi’s friends, her entanglement with Ayeni was never limited to transactional affection. They say she saw him as a source of security — not only financial, but social. The house she occupies, the staff who serve her, the status she carries in Abuja’s elite circles, all are attributed to her tie to him. Even when denied formal recognition, she continued to leverage that connection, refusing to relinquish it in word or deed.

At the height of their conflict, Adaobi’s mother allegedly pleaded with Ayeni to replace phones he had smashed, begged him for forgiveness when tensions threatened to boil over, and attended his office dressed elegantly to maintain visibility. One insider described the mother as “elaborately fearless,” someone who seemed unbothered by moral judgment and more focused on results.

To many of her critics, Adaobi does not simply want the luxury; she wants permanence without commitment. She appears to wield her dependence like a tool, playing on Ayeni’s guilt, his resources, and his public image, insisting on her place even as he insists on distancing himself. Her ability to remain physically present — living in his properties, frequently visiting his homes even after public fallout — distinguishes her from someone fighting for recognition, and aligns her with someone determined to preserve her access at all costs.

This orchestrated dependency, according to critics, reveals a moral erosion: not simply an opportunistic family, but one that has conflated ambition and entitlement, love and leverage, access and principle. The mother’s involvement complicates any argument that this is a romance gone wrong: it suggests a deeply embedded system of exploitation.

For Ayeni, the consequences have been serious and sustained. He once called this entanglement “one of the darkest moments” of his life, describing the family as his “greatest regret” in a televised interview. He accused both Adaobi and her mother of manipulation, emotional blackmail, and an unending sense of entitlement.

There have also been legal and reputational battles. Adaobi reportedly filed statements with the police, claiming harassment and intimidation. Ayeni’s camp, for its part, has denied several of her claims, painting a picture of a relationship replete with contradictions: on one hand, deep emotional entanglement; on the other, relentless exploitation.

Her friends say she blocks well-intended advice. Several have reportedly urged her to break free, reclaim her dignity, and build something independent of Ayeni. According to those close to her, she has gradually shut out those voices, preferring the access she still enjoys to the uncertainty that comes with cutting ties.

The question every critical observer is asking is simple: What is Adaobi really getting from keeping this connection alive? It is not only about the monthly stipend, though that is substantial. Beyond the cash, she benefits from physical spaces; houses, staff, and other material resources; that have enabled her to maintain a high-profile lifestyle without fully exposing vulnerability.

But the most baffling, most bewildering character in this entire sordid saga is Adaobi’s mother, the woman who flamboyantly calls herself Mrs. Princess Adaora Amam. She does not merely enable her daughter’s disasters; she escorts her into them with the confidence of someone utterly divorced from reality.

How does a woman who left her first marriage under scandal, and is knee-deep in crises with her second husband in Lagos, abandon her matrimonial home, her last claim to dignity, to go nest in her daughter’s lover’s house? And not just any lover: a fully married man, decades older, who has publicly humiliated them both, questioned the paternity of her granddaughter, and repeatedly denied them.

Yet instead of directing their rage at the person dragging them through the mud, Adaobi and her mother face the wrong direction entirely, charging at Ayeni’s wife, his girlfriend, and his associates with the fury of people determined to fight everyone except the man actually insulting them.

And floating above all this chaos is Madam Adaora’s grand delusion: the laughable insistence on calling herself Princess. A princess of where, exactly? Which kingdom? Which throne? Which lineage? Her behaviour alone betrays the truth. No woman born of pedigree behaves like this.

Her refusal to leave, even as her relationship with Ayeni deteriorates, signals a deeper truth. According to insiders, she has made a choice: humiliation is acceptable so long as stability remains. Rather than sever the bond, she persists. Rather than walk away, she tightens her grip.

The comparison to Regina Daniels’ widely publicized separation from Senator Ned Nwoko, by high society pundits, is particularly instructive. Unlike Adaobi, Regina walked away. Despite being younger and under intense scrutiny, she publicly asserted her worth, insisted on respect, and, when lines were crossed, removed herself from an untenable relationship.

Adaobi’s trajectory, by contrast, appears less about self-worth and more about dependency. While Regina seized agency, according to critics, Adaobi opted for survival, or at least the semblance of it. Where Regina’s exit was viewed by many as an act of self-respect, Adaobi’s tenacity has drawn condemnation as greed dressed in resilience.

Some commentators argue that Adaobi sees the relationship as a business, not a partnership. They suggest she took the same calculation approach that many ambitious people adopt in their careers: find a powerful benefactor, extract value, and secure long-term access.

What underlies this drama is a broader generational shift in how relationships are negotiated. Wealthy older men like Ayeni are no longer simply partners or benefactors; they are nodes in networks of social capital, power, and financial leverage. Younger women who grew up in a digital age, surrounded by public platforms and audience economies, understand this dynamic intuitively. They navigate relationships not only with hearts, but with spreadsheets: what I give, what I get, when I leave, whether I stay.

Adaobi and her mother, by many accounts, represent a sophisticated expression of that shift. They do not simply want to be loved; they want to be sustained. The stakes are both emotional and materially existential. They see Ayeni not just as a lover, but as an investment, a resource and the base of a lifestyle that may not be replicable elsewhere.

Their critics argue that the emotional intimacy has become secondary. What remains primary is the access: to money, property, and influence. They suggest that Adaobi’s repeated attempts to hold on, despite deep fractures, betray a transactional logic more than a romantic one.

Ayeni, on his part, is hardly a victim without agency. Even after describing his regret publicly, acknowledging both his culpability and the cost of their relationship, he is desperately seeking to reconcile with Adaobi. His critics, though, claim he misreckoned the depth of the desperation and ambition of both Adaobi and her mother.

Ayeni and Adaobi’s back and forth with each other certainly fits into a recurring pattern: powerful men drawn into emotionally volatile situations with younger women, only to be drawn back again. He appears to warn people publicly, justify himself in interviews, and attempt legal recourse, but those close to Adaobi say he has never severed the financial flow entirely.

This repeated dynamic raises deep questions about power: who has it, who uses it, and who sustains it. Ayeni wields resources; she wields proximity. He controls access; she exploits dependence. Their relationship becomes a site of perpetual negotiation, not of love, but of leverage.

And the moral cost is heavy. Whether one condemns her for her persistence or pities her for her dependence, the truth remains that their arrangement reflects a broader decay in relational trust. It suggests that love and money no longer occupy separate domains, but bleed into each other until the boundaries blur.

Adaobi Alagwu and her mother may be perceived by many as shameless gold diggers, but their strategy has been frighteningly effective. Through repeated demands, strategic positioning, and a refusal to relinquish access, they have turned Tunde Ayeni into a financial anchor for their ambitions.

When compared to the likes of Regina Daniels, who walked away from a high-profile political marriage with her dignity intact, Adaobi’s path reads less like a tale of emancipation than a study of calculated dependence. The contrast underscores a generational shift: whereas older norms emphasized discretion and commitment, newer norms exploit visibility and leverage. Adaobi and her mother appear to have mastered this new terrain, surviving scandal, humiliation and rejection because they view Ayeni not simply as a partner but as their lifeline.

If anything, their story demands that Nigerians examine more than their moral outrage. It calls for reflection on the power dynamics that govern modern relationships, especially when wealth, gender and ambition converge. It demands accountability for those who exploit, yes, but also for those who enable. Because the cost of this kind of symbiosis is not just personal, but societal: a corruption of affection, a redefinition of loyalty, and an erosion of trust in an age where money and love are dangerously intertwined.

society

Stakeholders Seek Urgent Reforms to Tackle Youth Unemployment at disrupTED EduKate Africa Summit

Stakeholders Seek Urgent Reforms to Tackle Youth Unemployment at disrupTED EduKate Africa Summit

By Ifeoma Ikem

Stakeholders in Nigeria’s education sector have called for urgent and scalable solutions to address the rising rate of youth unemployment, stressing the need for strengthened technical education and increased collaboration with the private sector to bridge existing skills gaps.

The call was made at the disrupTED EduKate Africa Summit 2026, a one-day leadership forum held at the University of Lagos, where participants examined the growing disconnect between education outcomes and labour market demands.

The summit brought together education leaders, private sector operators and development advocates to promote adaptive learning, practical skills acquisition and innovative financing models for Africa’s education sector.

Experts at the summit strongly advocated increased investment in technical and vocational education, noting that training programmes must reflect current industry realities and evolving labour market needs.

Speakers emphasised that Nigeria’s education system, particularly at the tertiary level, must urgently shift from certificate-driven learning to skills-based and experiential education aligned with global best practices.

Among the speakers were Deby Okoh, Regional Manager at Brunel University of London; Ashley Immanuel, Chief Operating Officer of Semicolon; Olapeju Ibekwe, Chief Executive Officer of Sterling One Foundation; and education advocate, Adetomi Soyinka.

The speakers highlighted the importance of continuous learning, teacher retraining and comprehensive curriculum reform to meet the demands of an increasingly technology-driven global economy.

They stressed that apprenticeship programmes, internships and hands-on training should be fully integrated into academic curricula, noting that over-reliance on theoretical qualifications has widened the employability gap among graduates.

In his remarks, Mr Tosin Adebisi, Director of EduKate Africa and convener of the summit, said the event was designed to challenge what he described as the education sector’s rigid attachment to outdated methods.

Adebisi said innovation must remain central to education reform, adding that stakeholders must rethink teaching methods, learning processes and approaches to solving challenges such as access to education, financing and employability.

He expressed confidence that sustainable solutions could be achieved through strong collaboration across education, private sector and development institutions.

Adebisi, alongside co-Director Mr Francis Omorojie, said the summit aimed at connecting stakeholders working across sectors to close existing skills and opportunity gaps for young people.

The summit also urged parents and educators to promote lifelong learning, critical thinking and adaptability among young people, stressing that education systems must evolve in line with global economic trends.

No fewer than 200 students from the University of Lagos, Lagos State University, Ojo, and other institutions participated in the summit, which was initially expected to host the Minister of Education, Dr Tunji Alausa.

In a welcome address, Prof. Olufemi Oloyede of the University of Lagos emphasised the need to shape young minds through innovation and positive thinking, noting that Africa’s development depends on the strategic use of its human and natural resources, as well as a shift towards creativity and innovation among youths.

society

Turning Point: Dr. Chris Okafor Resumes with Fresh Fire of the Spirit

Turning Point: Dr. Chris Okafor Resumes with Fresh Fire of the Spirit

-Steps onto the Grace Nation Pulpit After a Month-Long Honeymoon Retreat with Renewed Supernatural Power

By Sunday Adeyemi

The much-anticipated February 1, 2026 “Turning Point” service of Grace Nation has come and gone, but its impact remains deeply etched in the hearts of Grace Nation citizens across the world. The significance of the day was unmistakable—it marked the official return of the Generational Prophet of God and Senior Pastor of Grace Nation Global, Dr. Chris Okafor, to active ministerial duty as the Set Man of the commission.

The date was particularly symbolic, as Dr. Okafor had taken close to one month away from the pulpit following his wedding late last year. The period served not only as a honeymoon but also as a season of rest, reflection, and intimate fellowship with God in preparation for a greater spiritual assignment ahead.

The atmosphere at Grace Nation was electric as the Generational Prophet and his wife were received with a heroic welcome, accompanied by prophetic praise, joyful dancing, and fervent prayers. It was a celebration of return, renewal, and readiness.

In his opening remarks, Dr. Chris Okafor declared that he had returned to fully pursue the mandate God entrusted to him—winning souls for the Kingdom of God. He issued a strong warning to the kingdom of darkness, stating that light and darkness cannot coexist. According to him, the season ahead would witness intensified spiritual engagement, as the Kingdom of God advances and the forces of darkness lose ground.

“This time,” the Generational Prophet affirmed, “it will be total displacement of darkness, as the light of God shines brighter than ever.”

The Message: Turning Point

Delivering a powerful sermon titled “Turning Point,” Dr. Okafor explained that a turning point is defined as a moment when a decisive and beneficial change occurs in a situation. He emphasized that such moments are often preceded by battles.

According to him, battles do not necessarily arise because one is doing wrong, but because God desires to reveal His power and teach vital lessons through them. Every genuine battle, he noted, carries divine involvement and purpose.

Addressing the question “Why must I fight a battle?” Dr. Okafor explained that individuals who carry extraordinary grace often encounter greater challenges. “When you carry what others do not carry,” he said, “the battles that come your way are usually bigger.”

Characteristics of a Turning Point

The Generational Prophet highlighted that when a person is firmly rooted in God, no storm can uproot them. A strong spiritual foundation ensures that no battle can shake one’s destiny. He explained that prayer does not eliminate battles, but preparation through prayer guarantees victory on the evil day.

“Battles push you into your turning point when you are rooted in the Spirit,” he stated, adding that a prayerful life is essential for sustained victory and elevation.

A Supernatural Service

The Turning Point service witnessed an extraordinary move of the Holy Spirit in a fresh dimension. Deliverance, healings, miracles, restoration, and diverse testimonies filled the atmosphere as worshippers encountered the power of God during the Sunday service.

In a related development, Dr. Chris Okafor officially commissioned the ultra-modern church restaurant, Fourthman Foodies, dedicating it to God for the benefit and use of Grace Nation citizens worldwide.

The February 1 service has since been described by many as a defining moment—one that signals a new spiritual season for Grace Nation Global. https://www.facebook.com/share/v/1B2Eh6B6wo/

Sunday Adeyemi is a Lagos-based journalist and society writer. He writes from Lagos.

society

Adron Homes Hails Ondo State at 50, Celebrates Legacy of Excellence

Adron Homes Hails Ondo State at 50, Celebrates Legacy of Excellence

The Chairman, Board of Directors, Management, and staff of Adron Group have congratulated the Government and people of Ondo State on the celebration of its 50th anniversary, describing the milestone as a significant chapter in Nigeria’s federal history and a testament to visionary leadership, resilience, and purposeful development.

In a goodwill message issued to commemorate the Golden Jubilee, Adron Group noted that since its creation in 1976, Ondo State has consistently distinguished itself as a centre of honour, intellect, and enterprise. Fondly referred to as The Sunshine State, the state has produced generations of outstanding professionals, administrators, and national leaders whose contributions continue to shape Nigeria’s socio-economic and political development.

According to the company, the strength of Ondo State lies not only in its rich cultural heritage and intellectual depth, but also in the values of integrity, diligence, and excellence that define its people. These qualities, Adron noted, have remained the bedrock of the state’s enduring relevance and national impact over the past five decades.

Adron Group further commended the state’s renewed drive in recent years towards infrastructure development, economic diversification, industrial growth, and youth empowerment, describing these initiatives as indicators of a forward-looking, inclusive development agenda anchored in sustainability and long-term prosperity.

“As a corporate organisation committed to nation-building and sustainable development, Adron Group recognises Ondo State as a strategic partner in progress,” the statement read. “We commend His Excellency, Lucky Orimisan Aiyedatiwa, Executive Governor of Ondo State, and the leadership of the state at all levels for their dedication to public service and their commitment to the advancement of the people.”

As Ondo State marks its Golden Jubilee, Adron Group joined millions of well-wishers in celebrating a legacy of excellence, strength of character, and promise, while expressing optimism that the next fifty years will usher in greater milestones in economic vitality, social advancement, innovation, and enduring peace.

The company concluded by wishing the Government and people of Ondo State continued progress and prosperity, adding that the Sunshine State remains well-positioned to shine even brighter in the years ahead.

-

celebrity radar - gossips6 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips6 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

Business6 months ago

Business6 months agoBatsumi Travel CEO Lisa Sebogodi Wins Prestigious Africa Travel 100 Women Award

-

news6 months ago

news6 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING