society

Drug Abuse Among People With Disabilities: The Hidden Crisis Nigeria Is Yet to Address

Drug Abuse Among People With Disabilities: The Hidden Crisis Nigeria Is Yet to Address.

By George Omagbemi Sylvester | Published by saharaweeklyng.com

“Neglect, stigma and policy gaps are fueling substance misuse among Nigeria’s most vulnerable and silence is costing lives.”

Nigeria likes to talk about inclusion, but talk without action has a human cost and one that is rarely counted. Behind closed doors and in the margins of health statistics, drug and substance misuse is wreaking havoc on people with disabilities (PWDs) across the country. This is not an unfortunate footnote; it is a predictable outcome of exclusion (social, medical and legal) that we have chosen to ignore.

Global and local evidence points to the same uncomfortable truth: people with disabilities are at higher risk of substance use and are less likely to receive appropriate treatment. International studies show that adults with disabilities report disproportionately high rates of substance use and adverse mental health symptoms compared with their non-disabled peers. These patterns are mediated by chronic pain, untreated mental-health disorders, social isolation and poverty with all conditions common among Nigerian PWDs.

Why this happens is painfully simple. Many people with disabilities live with chronic pain or long-term health conditions for which medication is necessary; others face untreated depression, anxiety and trauma. When health systems are inaccessible, poorly resourced, or openly hostile, self-medication becomes an easy (and dangerous) option. Add stigma and social exclusion and the risk escalates: illicit substances, alcohol, codeine-laden cough syrups and diverted prescription drugs become stopgap “TREATMENTS” for pain, loneliness and despair. The World Health Organization explicitly warns that persons with disabilities are more likely to face risk factors for tobacco, alcohol and drug use because they are often left out of public health interventions.

In Nigeria the problem has particular features. National-level surveys and UN estimates indicate that drug use is widespread in the country: a sizeable share of Nigerians between 15 and 64 (measured in millions) are affected by drug misuse, and substances such as tramadol and codeine-based syrups have become common in both urban and rural settings. Meanwhile, enforcement-focused headlines about drug seizures and legislative crackdowns obscure the human reality: far too many people who need treatment cannot access it. UN reporting notes that globally only about one in eleven people with drug use disorders receive treatment — an equity gap that hits PWDs especially hard.

There are three converging failures driving this hidden crisis in Nigeria.

1. Health systems and services are inaccessible or ill-equipped.

Rehabilitation, mental-health care and substance-use treatment services in Nigeria are chronically underfunded and concentrated in a handful of urban centres. Even where services exist, they are rarely adapted for persons with sensory, cognitive or mobility impairments — meaning that facilities, intake procedures, therapy methods and communication approaches exclude those who most need help. Research in multiple settings has shown that substance-use screening and treatment must include disability accommodations and comprehensive pain management; otherwise, PWDs fall through the cracks.

2. Stigma and social isolation push vulnerable people into substance use.

Violence, neglect and discrimination against children and adults with disabilities are well documented. International studies report alarmingly high rates of abuse and neglect of disabled children and teenagers — environments that predispose survivors to substance misuse later in life. In Nigeria, cultural stigma combined with poverty and lack of social protection amplifies the risk: ostracised individuals may turn to substances to cope with trauma and exclusion.

3. Policy and legal frameworks exist but are not implemented or aligned.

Nigeria’s Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2018 created legal obligations to integrate and protect PWDs. That law, however, has not been matched by robust investment in disability-aware mental-health services, nor by targeted substance-use programs for PWDs. At the same time, the country’s current public conversation often leans toward punitive measures against drug offenders rather than public-health strategies that address addiction as a medical and social problem. Recent moves in the legislature to stiffen criminal penalties for trafficking, while addressing supply-side harms, risk further marginalising people who need treatment rather than punishment.

What must be done is clear, if politically uncomfortable: treat this as a public-health and human-rights emergency, not an embarrassing exception to be hidden.

First, expand access to disability-inclusive treatment. Health facilities and substance-use programs must be made physically and clinically accessible. That means ramps and sign-language interpretation, yes — but also adapting clinical screening tools, counseling approaches and pain-management strategies to different impairment types. International evidence shows that substance-use interventions that account for pain and comorbid mental disorders reduce misuse and improve outcomes; Nigeria must tailor these approaches and scale them beyond elite urban clinics.

Second, invest in community-based prevention and social protection. Poverty, unemployment and social isolation are key drivers. Cash transfers, supported employment schemes, community rehabilitation programs and family support can reduce the conditions that lead people to self-medicate. Civil-society organisations and disabled-persons organisations (DPOs) are best placed to guide culturally appropriate prevention work — they must be funded and partnered with, not sidelined.

Third, collect the right data. You cannot manage what you do not measure. National surveys and drug-control reports must disaggregate by disability status, impairment type and gender. That data gap means policymakers have no reliable estimate of the scale of the problem among PWDs — and therefore no political imperative to act. Recent Nigerian and international studies give us indications; what we need is systematic, routine surveillance integrated into national drug and health surveys.

Fourth, shift from punishment to treatment. Public policy must rebalance from criminalisation toward evidence-based treatment and harm reduction. Where trafficking and organised crime require law enforcement, do so — but not at the cost of denying care to people with addiction who are also living with disabilities. The human-rights implications of mandatory incarceration for people with mental-health comorbidities must be taken seriously.

Finally, we must break the silence. Families, communities and politicians treat disability as a private tragedy. Addiction among PWDs becomes doubly invisible: the stigma of disability plus the stigma of drug use. Nigeria’s media, universities and policy forums must expose this reality and hold leaders accountable for the gap between the law’s promise and the lived experience of millions.

To the policymakers reading this: the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities Act 2018 is not a placard to be posted on ministry walls — it is a legal platform that demands resources, enforcement and services. To the NDLEA and health ministries: seize the moment to partner with DPOs, donors and community groups to pilot disability-inclusive treatment models that can be scaled nationwide. To civil society: press for data, for pilots and for funding that reaches grassroots organisations.

Addiction among people with disabilities is not a “special interest” issue — it is a test of our humanity. If a nation claims to value inclusion, then it must protect the most vulnerable from a tide of substances, neglect and institutional failure. Anything less is hypocrisy.

If Nigeria does not act, the toll will grow: more lives shortened, families broken and talents wasted. But if we choose compassion, transparency and evidence, we can transform a hidden crisis into a model of inclusive care. The legislation is on the books; now let our actions prove that we meant it.

society

Stop Means Stop”: Legal Experts Warn Ignoring ‘Stop’ During Intimate Acts Can Be Criminally Punishable

“Stop Means Stop”: Legal Experts Warn Ignoring ‘Stop’ During Intimate Acts Can Be Criminally Punishable

By George Omagbemi Sylvester | Published by SaharaWeeklyNG

“Grounded in international law and consent principles, legal authorities stress that continuing sexual activity after a partner withdraws consent may constitute sexual assault and lead to imprisonment.”

A growing body of legal interpretation and expert opinion reaffirm that consent in intimate encounters is not a one-off event but an ongoing requirement; withdrawn at any time by either participant. Legal practitioners and rights advocates are increasingly warning that if one partner clearly says “stop” during sexual activity and the other continues, this conduct can constitute a criminal offence with significant penalties, including imprisonment.

Consent must be “a voluntary agreement to engage in the sexual activity in question,” and crucially can be revoked at any stage. Once a partner expresses withdrawal of consent (by words like “stop” or by unmistakable conduct) the other party is legally obligated to cease all activity immediately. Failure to respect this is widely recognised in multiple legal jurisdictions as sexual assault or rape.

Professor Deborah Rhode, a prominent authority on legal ethics, has stated: “Respect for autonomy and bodily integrity lies at the core of consent law. Ignoring a partner’s withdrawal of consent undermines basic personal freedoms and is treated as a serious offence in criminal law.”

According to experts, this legal principle is not limited to strangers but applies equally to long-term partners and spouses. The Criminal Code in many countries explicitly rejects implied or blanket consent based on relationship status.

Human rights lawyer Amal Clooney has similarly emphasised that clear communication and mutual agreement are essential, and that “once consent is withdrawn, any continued sexual activity crosses the line into criminal conduct.”

This means that in places where consent law is well-established, ignoring an explicit “stop” can lead to charges of sexual assault, with courts interpreting such conduct as a violation of an individual’s autonomy and dignity.

The issue has gained media and legal attention in recent years across numerous jurisdictions (including Canada, parts of Europe, and reform discussions in U.S. states) as courts and legislatures clarify that sexual consent is continuous and revocable at any time. Although no globally consolidated database exists of individual cases tied specifically to a news report on this warning, reputable legal frameworks consistently reinforce that continuing after “stop” is unlawful.

The subject engages legal scholars, criminal law practitioners, human rights experts, and statutory bodies advocating sexual violence prevention. Law enforcement agencies and prosecutors may pursue charges when clear evidence shows that consent was withdrawn and ignored.

In practice, consent frameworks require that the person initiating or continuing sexual activity take reasonable steps to ensure ongoing affirmation of willingness. Silence, passive behaviour, or failure to stop when asked cannot substitute for ongoing consent.

In summary, the legal maxim is clear: verbal or unambiguous withdrawal of consent must be respected. Ignoring it shifts the encounter from consensual to criminal, potentially resulting in serious legal consequences including imprisonment.

society

Lagos Family Property Dispute Turns Violent After Death of Omotayo Ojo

Lagos Family Property Dispute Turns Violent After Death of Chief Omotayo Ojo

By Ifeoma Ikem

A festering family dispute over property has escalated into a series of violent attacks in Lagos, leaving residents of a contested apartment in fear for their safety.

Mrs. Omotayo-Ojo-Alolagbe (Nee Omotayo-Ojo) the third child and first daughter of the late Omotayo Ojo, has alleged repeated assaults and destruction of property by her siblings from her father’s other marriages.

According to her account, hostility against her began while her father was still alive, allegedly fueled by the affection and support he showed her. She claimed that tensions worsened after his death in 2019.

Mrs. Alolagbe stated that her late father had given her a particular apartment during his lifetime, assuring her she would not suffer hardship, especially after her husband left the marriage. She said the property became her primary source of livelihood and shelter.

However, she alleged that her siblings had sold off several other family properties and were determined to dispossess her of the apartment allocated to her by their father.

The dispute reportedly turned violent on Nov. 15, 2025, when unknown persons allegedly attacked the building. She said the incident prompted her to petition the Chief Judge of Lagos State and the Commissioner of Police.

Despite the pending legal proceedings, she alleged that another attack occurred on Jan. 21, 2026. During that incident, parts of the building were vandalised, including the walkway and the main gate, which was reportedly removed.

A third attack was said to have taken place on Feb.18, 2026, during which the roof, gates, and sections of the walkway were allegedly dismantled. Residents were reportedly assaulted, and some were allegedly forced to part with money under duress.

Tenants in the apartment complex are said to be living in fear amid the repeated invasions, expressing concern over their safety and uncertainty about further violence.

Mrs. Alolagbe alleged that the attacks were led by a man identified as Mr. Alliu, popularly known as aka “Champion,” whom she described as a political thug. She claimed he arrived with a group of about 50 men, allegedly brandishing weapons and breaking bottles to intimidate residents.

She further alleged that the group boasted of connections with senior police officers, politicians in Lagos State, and even the presidency, claiming they were untouchable.

According to her, some arrests were initially made following the incidents, but the suspects were later released. She expressed concern that the alleged perpetrators continue to threaten her, making it difficult for her to move freely.

She also disclosed that during a meeting on Feb. 23, 2026, an Area Commander reportedly told her that little could be done because the matter was already before a court of law.

The development has raised concerns about the enforcement of law and order in civil disputes that degenerate into violence, particularly when court cases are pending.

As tensions persist, residents and observers are calling on relevant authorities to ensure the safety of lives and properties ,while allowing the courts to determine ownership and bring lasting resolution to the dispute.

society

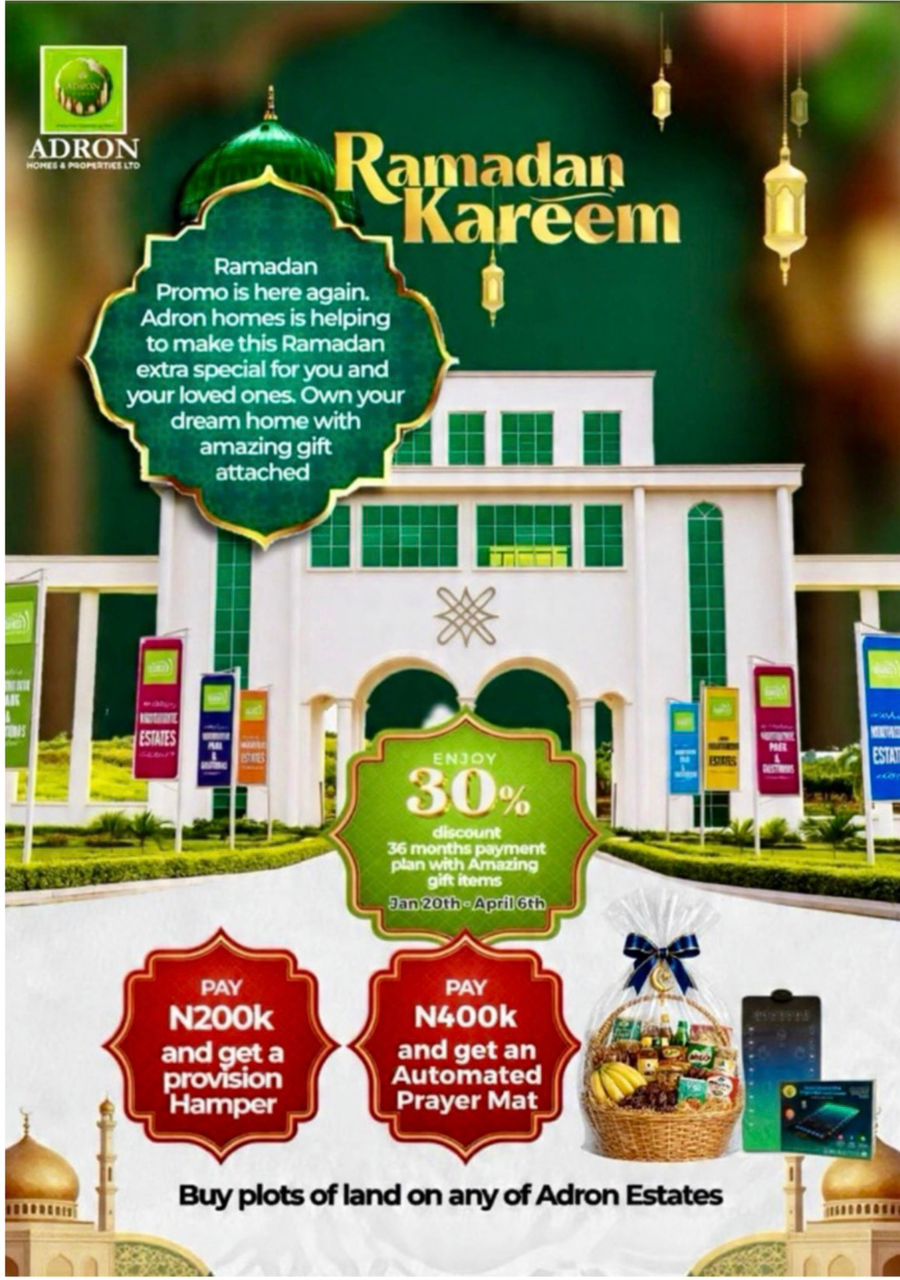

Adron Homes Introduces Special Ramadan Offer with Discounts and Gift Rewards

Adron Homes Introduces Special Ramadan Offer with Discounts and Gift Rewards

As the holy month of Ramadan inspires reflection, sacrifice, and generosity, Adron Homes and Properties Limited has unveiled its special Ramadan Promo, encouraging families, investors, and aspiring homeowners to move beyond seasonal gestures and embrace property ownership as a lasting investment in their future.

The company stated that the Ramadan campaign, running from January 20th to April 6th, 2026, is designed to help Nigerians build long-term value and stability through accessible real estate opportunities. The initiative offers generous discounts, flexible payment structures, and meaningful Ramadan-themed gifts across its estates and housing projects nationwide.

Under the promo structure, clients enjoy a 30% discount on land purchases alongside a convenient 36-month flexible payment plan, making ownership more affordable and stress-free.

In the spirit of the season, the company has also attached thoughtful rewards to qualifying payments. Clients who pay ₦200,000 receive a Provision Hamper to support their household during the fasting period, while those who pay ₦400,000 receive an Automated Prayer Mat to enhance their spiritual experience throughout Ramadan.

According to the company, the Ramadan Promo reflects its commitment to aligning lifestyle, faith, and financial growth, enabling Nigerians at home and in the diaspora to secure appreciating assets while observing a season centered on discipline and forward planning.

Reiterating its dedication to secure land titles, prime locations, and affordable pricing, Adron Homes urged prospective buyers to take advantage of the limited-time Ramadan campaign to build a future grounded in stability, prosperity, and generational wealth.

This promo covers estates located in Lagos, Shimawa, Sagamu, Atan–Ota, Papalanto, Abeokuta, Ibadan, Osun, Ekiti, Abuja, Nasarawa, and Niger states.

As Ramadan calls for purposeful living and wise decisions, Adron Homes is redefining the season, transforming reflection into investment and faith into a lasting legacy.

-

celebrity radar - gossips6 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips6 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society5 months ago

society5 months agoReligion: Africa’s Oldest Weapon of Enslavement and the Forgotten Truth

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

news7 months ago

news7 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING