society

A MORNING OF CARNAGE by Chief Femi Fani-Kayode

A MORNING OF CARNAGE by Chief Femi Fani-Kayode

Sixty years ago, in the early hours of the morning of January 15th 1966, a coup d’etat took place in Nigeria which resulted in the murder of a number of leading political figures and senior army officers.

This was the first coup in the history of our country and 98 per cent of the officers that planned and led it were from a particular ethnic nationality in the country.

According to Max Siollun, a notable and respected historian whose primary source of information was the Police report compiled by the Police’s Special Branch after the failure of the coup, during the course of the investigation and after the mutineers had been arrested and detained, names of the leaders of the mutiny were as follows:

Major Emmanuel Arinze Ifeajuna,

Major Chukwuemeka Kaduna Nzeogwu,

Major Chris Anuforo,

Major Tim Onwutuegwu,

Major Chudi Sokei,

Major Adewale Ademoyega,

Major Don Okafor,

Major John Obieno,

Captain Ben Gbuli,

Captain Emmanuel Nwobosi,

Captain Chukwuka,

and Lt. Oguchi.

It is important to point out that I saw the Special Branch report myself and I can confirm Siollun’s findings.

These were indeed the names of ALL the leaders of the January 15th 1966 mutiny and all other lists are FAKE.

The names of those that they murdered in cold blood or abducted were as follows.

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, the Prime Minister of Nigeria (murdered),

Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto and the Premier of the Old Northern Region (murdered),

Sir Kashim Ibrahim, the Shettima of Borno and the Governor of the Old Northern Region (abducted),

Chief Samuel Ladoke Akintola, the Aare Ana Kakanfo of Yorubaland and the Premier of the Old Western Region (murdered),

Chief Remilekun Adetokunboh Fani-Kayode SAN, Q.C. CON, the Balogun of Ife, the Deputy Premier of the Old Western Region, the Regional Minister for Local Government and Chieftaincy Affairs and my beloved father (abducted),

Chief Festus Samuel Okotie-Eboh, the Oguwa of the Itsekiris and the Minister of Finance of Nigeria (murdered),

Brigadier Samuel Adesujo Ademulegun, Commander of the 1st Brigade, Nigerian Army (murdered),

Brigadier Zakariya Maimalari, Commander of the 2nd Brigade, Nigerian Army (murdered),

Colonel James Pam (murdered),

Colonel Ralph Sodeinde (murdered),

Colonel Arthur Unegbe (murdered),

Colonel Kur Mohammed (murdered),

Lt. Colonel Abogo Largema (murdered),

Alhaja Hafsatu Bello, the wife of the Sardauna of Sokoto (murdered),

Alhaji Zarumi, traditional bodyguard of the Sardauna of Sokoto (murdered),

Mrs. Lateefat Ademulegun, the wife of Brigadier Ademulegun who was 8 months pregnant at the time (murdered),

Ahmed B. Musa (murdered),

Ahmed Pategi (murdered),

Sgt. Daramola Oyegoke (murdered),

Police Constable Yohana Garkawa (murdered),

Police Constable Musa Nimzo (murdered),

Police Constable Akpan Anduka (murdered),

Police Constable Hagai Lai (murdered),

and Police Constable Philip Lewande (murdered).

In order to reflect the callousness of the mutineers permit me to share under what circumstances some of their victims were murdered and abducted.

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was abducted from his home, beaten, mocked, tortured, forced to drink alcohol, humiliated and murdered after which his body was dumped in a bush along the Lagos-Abeokuta road.

Sir Ahmadu Bello was killed in the sanctity of his own home with his wife Hafsatu and his loyal security assistant Zurumi.

Zurumi drew his sword to defend his principal whilst Hafsatu threw her body over her dear husband in an attempt to protect him from the bullets.

Chief S. L. Akintola was gunned down as he stepped out of his house in the presence of his family and Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh was beaten, brutalised, abducted from his home, maimed and murdered and his body was dumped in a bush.

Brigadier Zakariya Maimalari had held a cocktail party in his home the evening before which was attended by some of the young officers that went back to his house early the following morning and murdered him.

Brigadier Samuel Ademulegun was shot to death at home, in his bedroom and in his matrimonial bed along with his eight-month pregnant wife Lateefat.

Colonel Shodeinde was murdered in Ikoyi hotel whilst Col. Pam was abducted from his home and murdered in a bush.

Most of the individuals that were killed that morning were subjected to a degree of humiliation, shame and torture that was so horrendous that I am constrained to decline from sharing them in this contribution.

The mutineers came to our home as well which at that time was the official residence of the Deputy Premier of the Old Western Region and which remains there till today.

After storming our house and almost killing my brother, sister and me, they beat, brutalised and abducted my father Chief Remi Fani-Kayode.

What I witnessed that morning was traumatic and devastating and, of course, what the entire nation witnessed was horrific.

It was a morning of carnage, barbarity and terror.

Those events set in motion a cycle of carnage which changed our entire history and the consequences remain with us till this day.

It was a sad and terrible morning and one of blood and slaughter.

My recollection of the events in our home is as follows.

At around 2.00 a.m. my mother, Chief (Mrs.) Adia Aduni Fani-Kayode, came into the bedroom which I shared with my older brother, Rotimi and my younger sister Toyin. I was six years old at the time.

My other older brother, Akinola, whom we fondly reffered to as Akins, was not with us that night because he was a border at Kings College, Lagos whilst my other younger sister Tolulope Fani-Kayode was not born until one year later!

The lights had been cut off by the mutineers so we were in complete darkness and all we could see and hear were the headlights from three or four large and heavy trucks with big loud engines.

The official residence of the Deputy Premier had a very long drive so it took the vehicles a while to reach us.

We saw four sets of headlights and heard the engines of four lorries drive up the drive-way.

The occupants of the lorries, who were uniformed men who carried torches, positioned themselves and prepared to storm our home whilst calling my fathers name and ordering him to come out.

My father courageously went out to meet them after he had called us together, prayed for us and explained to us that since it was him they wanted he must go out there.

He explained that he would rather go out to meet them and, if necessary, meet his death than let them come into the house to shoot or harm us all.

The minute he stepped out they brutalised him. I witnessed this. They beat him, tied him up and threw him into one of the lorries.

The first thing they said to him as he stepped out was “where are your thugs now Fani-Power?”

My father’s response was typical of him, sharp and to the point. He said, “I don’t have thugs, only gentlemen.”

I think this annoyed them and made them brutalise him even more. They tied him up, threw him in the back of the lorry and then stormed the house.

When they got into the house they ransacked every nook and cranny, shooting into the ceiling and wardrobes.

They were very brutal and frightful and we were terrified.

My mother was screaming and crying from the balcony because all she could do was focus on her husband who was in the back of the truck downstairs. There is little doubt that she loved him more than life itself.

“Don’t kill him, don’t kill him!!” she kept screaming at them. I can still visualise this and hear her voice pleading, screaming and crying.

I didn’t know where my brother or sister were at this point because the house was in total chaos.

I was just six years old and I was standing there in the middle of the passage upstairs in the house by my parents bedroom, surrounded by uniformed men who were ransacking the whole place and terrorising my family.

Then out of the blue something extraordinary happened. All of a sudden one of the soldiers came up to me, put his hand on my head and said: “don’t worry, we won’t kill your father, stop crying.”

He said this to me three times. After he said it the third time I looked in his eyes and I stopped crying.

This was because he gave me hope and he spoke with kindness and compassion. At that point all the fear and trepidation left me.

With new-found confidence I went rushing to my mother who was still screaming on the balcony and told her to stop crying because the soldier had promised that they would not kill my father and that everything would be okay.

I held on to the words of that soldier and that morning, despite all that was going on around me, I never cried again.

Four years ago when he was still alive I made contact with and spoke to Captain Nwobosi, the mutineer who led the team to our house and that led the Ibadan operation that night about these events.

He confirmed my recollection of what happened in our house saying that he remembered listening to my mother screaming and watching me cry.

He claimed that he was the officer that had comforted me and assured me that my father would not be killed.

I have no way of confirming if it was really him but I have no reason to doubt his words.

He later asked me to write the foreword of his book which sadly he never launched or released because he passed away a few months later.

The mutineers took my father away and as the lorry drove off my mother kept on wailing and crying and so was everyone else in the house except for me.

From there they went to the home of Chief S.L. Akintola a great statesman and nationalist and a very dear uncle of mine.

My mother had phoned Akintola to inform him of what had happened in our home.

She was sceaming down the phone asking where her husband had been taken and by this time she was quite hysterical.

Chief Akintola tried to calm her down assuring her that all would be well.

When they got to Akintola’s house he already knew that they were coming and he was prepared for them.

Instead of coming out to meet them, he had stationed some of his policemen inside the house and they started shooting.

A gun battle ensued and consequently the mutineers were delayed by at least one hour.

According to the Special Branch reports and the official statements of the mutineers that survived that night and that were involved in the operation their plan had been to pick up my father and Chief Akintola from their homes in Ibadan, take them to Lagos, gather them together with the other political leaders that had been abducted and then execute them all together.

The difficulty they had was that Akintola resisted them and he and his policemen ended up wounding two of the soldiers that came to his home.

One of the soldiers, whose name was apparently James, had his fingers blown off and the other had his ear blown off.

After some time Akintola’s ammunition ran out and the shooting stopped.

His policemen stood down and they surrendered. He came out waving a white handkerchief and the minute he stepped out they just slaughtered him.

My father witnessed Akintola’s cold-blooded murder in utter shock, disbelief and horror because he was tied up in the back of the lorry from where he could see everything that transpired.

The soldiers were apparently enraged by the fact that two of their men had been wounded and that Akintola resisted and delayed them.

After they killed him they moved on to Lagos with my father.

When they got there they drove to the Officer’s Mess at Dodan Barracks in Ikoyi where they tied him up, sat him on the floor of a room, and placed him under close arrest by surrounding him with six very hostile and abusive soldiers.

Thankfully about two hours later he was rescued, after a dramatic gun battle, by loyalist troops led by one Lt. Tokida who stormed the room with his men and who was under the command of Captain Paul Tarfa (as he then was).

They had been ordered to free my father by Lt. Col. Yakubu Gowon who was still in control of the majority of troops in Dodan Barracks and who remained loyal to the Federal Government.

Bullets flew everywhere in the room during the gunfight that ensued whilst my father was tied up in the middle of the floor with no cover. All that yet not one bullet touched him!

This was clearly the Finger of God and once again divine providence as under normal circumstances few could have escaped or survived such an encounter without being killed either by direct fire or a stray bullet. For this I give God the glory.

Meanwhile three of the soldiers that had tied my father up and placed him under guard in that room were killed right before his eyes and two of Takoda’s troops that stormed the room to save him lost their lives in the encounter.

At this point permit me to mention the fact that outside of my father, providence also smiled favourably upon and delivered Sir Kashim Ibrahim, the Shettima of Borno and the Governor of the Old Northern Region from death that morning.

He was abducted from his home in Kaduna by the mutineers but was later rescued by loyalist troops.

When the mutineers took my father away everyone in our home thought he had been killed.

The next morning a handful of policemen came and took us to the house of my mother’s first cousin, Justice Atanda Fatai-Williams, who was a judge of the Western Region at the time. He later became the Chief Justice of Nigeria.

From there we were taken to the home of Justice Adenekan Ademola, another High Court judge at the time, who was a very close friend of my father, who later became a Judge of the Court of Appeal and whose father, Sir Adetokunboh Ademola, was to later become the first Nigerian Chief Justice of the Federation.

At this point the whole country had been thrown into confusion and no one knew what was going on.

We heard lots of stories and did not know what to make of what anymore. There was chaos and confusion and the entire nation was gripped by fear.

Two days later my father finally called us on the telephone and he told us that he was okay.

When we heard his voice, I kept telling my mother “I told you, I told you.”

Justice Ademola and his dear wife who was my mother’s best friend, a Ghanaian lady by the name of Mrs. Frances Ademola (nee Quarshie-Idun) whom we fondly called Aunty Frances and whose father was Justice Samuel Okai Quarshie-Idun, the Chief Justice of the High Court of Western Nigeria and later President of the East African Court of Appeal, wept with joy.

My mother was also weeping as were my brother and sister and I just kept rejoicing because I knew that he would not be killed and I had told them all.

I believe that whoever that soldier was that promised me that my father would not be killed was used by God to convey a message to me that morning even in the midst of the mayhem and fear. I believe that God spoke through him that night.

Whoever he was the man spoke with confidence and authority and this constrains me to believe that he was a commissioned officer or a man in authority.

What happened on the night of January 15th 1966 was indefensible, unjustifiable, unacceptable, unnecessary, unprovoked and utterly barbaric.

It set off a cycle of events which had cataclysmic consequences for our country and which we are still reeling from today.

It arrested our development as a people and our political evolution as a country.

Had it not happened our history would have been very different. May we never see such a thing again.

(Chief Femi Fani-Kayode is the Sadaukin Shinkafi, the Wakilin Doka Potiskum, the Otunba Joga Orile, the Aare Ajagunla of Otun Ekiti, a lawyer, a former Senior Special Assistant on Public Affairs to President Olusegun Obasanjo, a former Minister of Culture and Tourism of Nigeria, a former Minister of Aviation of Nigeria and an Ambassador-Designate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria)

society

Stop Means Stop”: Legal Experts Warn Ignoring ‘Stop’ During Intimate Acts Can Be Criminally Punishable

“Stop Means Stop”: Legal Experts Warn Ignoring ‘Stop’ During Intimate Acts Can Be Criminally Punishable

By George Omagbemi Sylvester | Published by SaharaWeeklyNG

“Grounded in international law and consent principles, legal authorities stress that continuing sexual activity after a partner withdraws consent may constitute sexual assault and lead to imprisonment.”

A growing body of legal interpretation and expert opinion reaffirm that consent in intimate encounters is not a one-off event but an ongoing requirement; withdrawn at any time by either participant. Legal practitioners and rights advocates are increasingly warning that if one partner clearly says “stop” during sexual activity and the other continues, this conduct can constitute a criminal offence with significant penalties, including imprisonment.

Consent must be “a voluntary agreement to engage in the sexual activity in question,” and crucially can be revoked at any stage. Once a partner expresses withdrawal of consent (by words like “stop” or by unmistakable conduct) the other party is legally obligated to cease all activity immediately. Failure to respect this is widely recognised in multiple legal jurisdictions as sexual assault or rape.

Professor Deborah Rhode, a prominent authority on legal ethics, has stated: “Respect for autonomy and bodily integrity lies at the core of consent law. Ignoring a partner’s withdrawal of consent undermines basic personal freedoms and is treated as a serious offence in criminal law.”

According to experts, this legal principle is not limited to strangers but applies equally to long-term partners and spouses. The Criminal Code in many countries explicitly rejects implied or blanket consent based on relationship status.

Human rights lawyer Amal Clooney has similarly emphasised that clear communication and mutual agreement are essential, and that “once consent is withdrawn, any continued sexual activity crosses the line into criminal conduct.”

This means that in places where consent law is well-established, ignoring an explicit “stop” can lead to charges of sexual assault, with courts interpreting such conduct as a violation of an individual’s autonomy and dignity.

The issue has gained media and legal attention in recent years across numerous jurisdictions (including Canada, parts of Europe, and reform discussions in U.S. states) as courts and legislatures clarify that sexual consent is continuous and revocable at any time. Although no globally consolidated database exists of individual cases tied specifically to a news report on this warning, reputable legal frameworks consistently reinforce that continuing after “stop” is unlawful.

The subject engages legal scholars, criminal law practitioners, human rights experts, and statutory bodies advocating sexual violence prevention. Law enforcement agencies and prosecutors may pursue charges when clear evidence shows that consent was withdrawn and ignored.

In practice, consent frameworks require that the person initiating or continuing sexual activity take reasonable steps to ensure ongoing affirmation of willingness. Silence, passive behaviour, or failure to stop when asked cannot substitute for ongoing consent.

In summary, the legal maxim is clear: verbal or unambiguous withdrawal of consent must be respected. Ignoring it shifts the encounter from consensual to criminal, potentially resulting in serious legal consequences including imprisonment.

society

Lagos Family Property Dispute Turns Violent After Death of Omotayo Ojo

Lagos Family Property Dispute Turns Violent After Death of Chief Omotayo Ojo

By Ifeoma Ikem

A festering family dispute over property has escalated into a series of violent attacks in Lagos, leaving residents of a contested apartment in fear for their safety.

Mrs. Omotayo-Ojo-Alolagbe (Nee Omotayo-Ojo) the third child and first daughter of the late Omotayo Ojo, has alleged repeated assaults and destruction of property by her siblings from her father’s other marriages.

According to her account, hostility against her began while her father was still alive, allegedly fueled by the affection and support he showed her. She claimed that tensions worsened after his death in 2019.

Mrs. Alolagbe stated that her late father had given her a particular apartment during his lifetime, assuring her she would not suffer hardship, especially after her husband left the marriage. She said the property became her primary source of livelihood and shelter.

However, she alleged that her siblings had sold off several other family properties and were determined to dispossess her of the apartment allocated to her by their father.

The dispute reportedly turned violent on Nov. 15, 2025, when unknown persons allegedly attacked the building. She said the incident prompted her to petition the Chief Judge of Lagos State and the Commissioner of Police.

Despite the pending legal proceedings, she alleged that another attack occurred on Jan. 21, 2026. During that incident, parts of the building were vandalised, including the walkway and the main gate, which was reportedly removed.

A third attack was said to have taken place on Feb.18, 2026, during which the roof, gates, and sections of the walkway were allegedly dismantled. Residents were reportedly assaulted, and some were allegedly forced to part with money under duress.

Tenants in the apartment complex are said to be living in fear amid the repeated invasions, expressing concern over their safety and uncertainty about further violence.

Mrs. Alolagbe alleged that the attacks were led by a man identified as Mr. Alliu, popularly known as aka “Champion,” whom she described as a political thug. She claimed he arrived with a group of about 50 men, allegedly brandishing weapons and breaking bottles to intimidate residents.

She further alleged that the group boasted of connections with senior police officers, politicians in Lagos State, and even the presidency, claiming they were untouchable.

According to her, some arrests were initially made following the incidents, but the suspects were later released. She expressed concern that the alleged perpetrators continue to threaten her, making it difficult for her to move freely.

She also disclosed that during a meeting on Feb. 23, 2026, an Area Commander reportedly told her that little could be done because the matter was already before a court of law.

The development has raised concerns about the enforcement of law and order in civil disputes that degenerate into violence, particularly when court cases are pending.

As tensions persist, residents and observers are calling on relevant authorities to ensure the safety of lives and properties ,while allowing the courts to determine ownership and bring lasting resolution to the dispute.

society

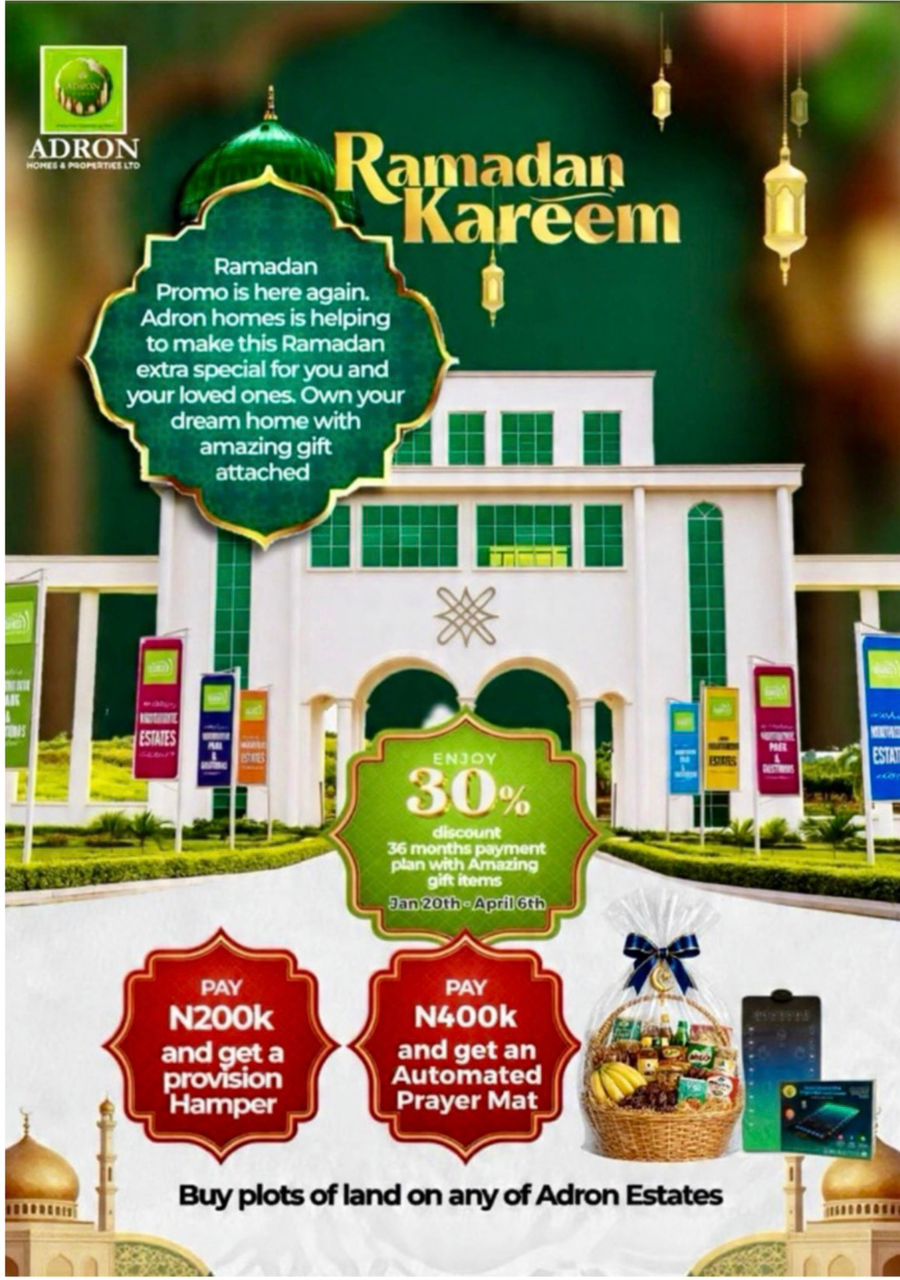

Adron Homes Introduces Special Ramadan Offer with Discounts and Gift Rewards

Adron Homes Introduces Special Ramadan Offer with Discounts and Gift Rewards

As the holy month of Ramadan inspires reflection, sacrifice, and generosity, Adron Homes and Properties Limited has unveiled its special Ramadan Promo, encouraging families, investors, and aspiring homeowners to move beyond seasonal gestures and embrace property ownership as a lasting investment in their future.

The company stated that the Ramadan campaign, running from January 20th to April 6th, 2026, is designed to help Nigerians build long-term value and stability through accessible real estate opportunities. The initiative offers generous discounts, flexible payment structures, and meaningful Ramadan-themed gifts across its estates and housing projects nationwide.

Under the promo structure, clients enjoy a 30% discount on land purchases alongside a convenient 36-month flexible payment plan, making ownership more affordable and stress-free.

In the spirit of the season, the company has also attached thoughtful rewards to qualifying payments. Clients who pay ₦200,000 receive a Provision Hamper to support their household during the fasting period, while those who pay ₦400,000 receive an Automated Prayer Mat to enhance their spiritual experience throughout Ramadan.

According to the company, the Ramadan Promo reflects its commitment to aligning lifestyle, faith, and financial growth, enabling Nigerians at home and in the diaspora to secure appreciating assets while observing a season centered on discipline and forward planning.

Reiterating its dedication to secure land titles, prime locations, and affordable pricing, Adron Homes urged prospective buyers to take advantage of the limited-time Ramadan campaign to build a future grounded in stability, prosperity, and generational wealth.

This promo covers estates located in Lagos, Shimawa, Sagamu, Atan–Ota, Papalanto, Abeokuta, Ibadan, Osun, Ekiti, Abuja, Nasarawa, and Niger states.

As Ramadan calls for purposeful living and wise decisions, Adron Homes is redefining the season, transforming reflection into investment and faith into a lasting legacy.

-

celebrity radar - gossips6 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips6 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society5 months ago

society5 months agoReligion: Africa’s Oldest Weapon of Enslavement and the Forgotten Truth

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

news7 months ago

news7 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING