society

Islamic Teacher Caught On Camera Defiling 5-Year-Old Girl In Lagos (Photo)

A 43-year-old Islamic studies teacher Abdulsalam Salaudeen has been arrested by the police for defiling a five-year-old girl.

Salaudeen, who lives 16, Awoyemi Street on Igando Road, Ikotun Lagos, was recorded on video while engaging in the act.

The suspected pedophile was allegedly engaged to teach the girl Islamic studies.

A Good Samaritan last Friday took the video evidence to the headquarters of the Lagos State Police Command.

After watching the heart-rending video, Commissioner of Police (CP) Imohimi Edgal, directed the command’s undercover operatives attached to the State Intelligence Bureau to immediately arrest the culprit and hand him over to the Gender Section for detailed investigation.

The operatives went in search of Salaudeen and arrested him near a mosque in Igando, a suburb of Lagos.

A statement by police spokesman Chike Oti, a Chief Superintendent (CSP), said Salaudeen was taken to the Gender Unit, where the Officer-in-Charge, Abimbola Williams, an Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP) confronted him with the video of him defiling the child by penetrating her anus and private parts.

“On seeing himself captured like an actor in a movie, the suspect broke down in tears and owned up to the crime,” Oti said.

The case, he added, will be charged to court as soon as the investigation is concluded.

Oti said: “The CP, while commending the courageous act of the good Nigerian, warned parents and guardians to keep constant watch over their children and wards.

“Nobody should be trusted. Be friends with your children and let them be free to share things with you.

“Do not cover up any crime, no matter who is involved. Raise the alarm on child molesters in your neighbourhood so they can face the law and other nursing such thoughts can be deterred.”

society

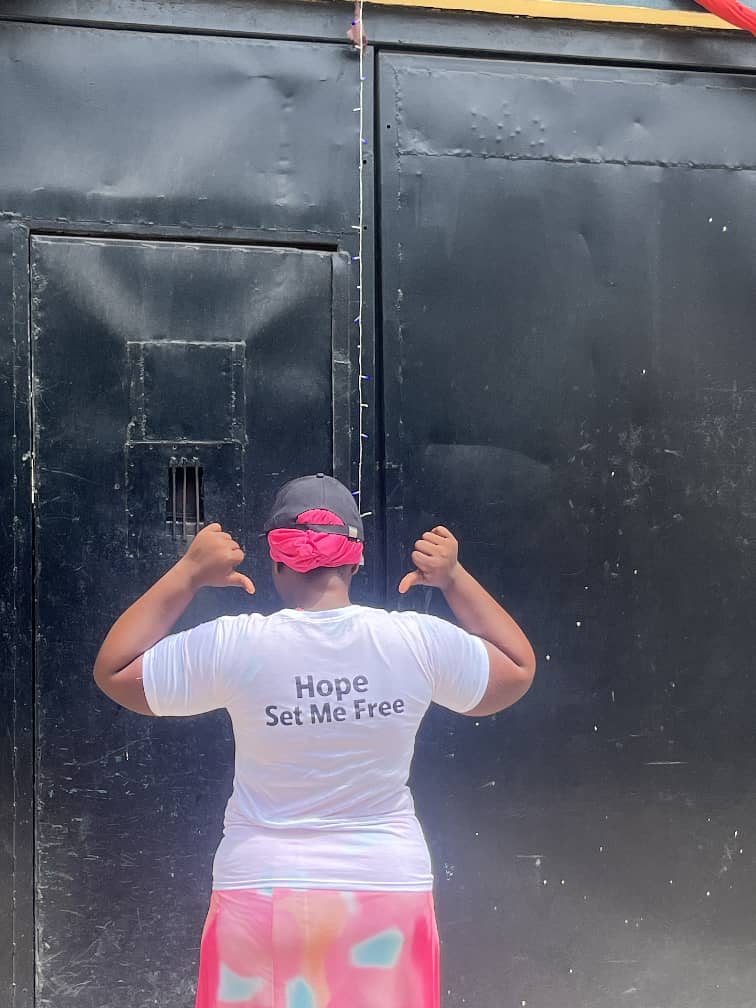

HOPE BEYOND THE WALLS 2026: ASSOCIATION OF MODELS SUCCESSFULLY SECURES RELEASE OF AN INMATE, CALLS FOR CONTINUED SUPPORT

HOPE BEYOND THE WALLS 2026: ASSOCIATION OF MODELS SUCCESSFULLY SECURES RELEASE OF AN INMATE, CALLS FOR CONTINUED SUPPORT

The Association of Models (AOMNGO) proudly announces the successful completion of the first edition of Hope Beyond the Walls 2026, a humanitarian initiative dedicated to restoring hope and freedom to deserving inmates.

Despite enormous challenges, financial pressure, emotional strain, and operational stress, the organization remained committed to its mission. Through perseverance, faith, and collective support, one inmate has successfully regained freedom a powerful reminder that hope is stronger than circumstance.

This milestone did not come easily.

Behind the scenes were weeks of coordination, advocacy, fundraising, documentation, and intense engagement. There were moments of uncertainty, but the determination to give someone a second chance kept the vision alive.

Today, the Association of Models gives heartfelt appreciation to all partners and sponsors, both locally and internationally, who stood with us mentally, financially, morally, and physically.

Special Recognition and Appreciation To:

Correctional Service Zonal Headquarters Zone A Ikoyi

Esan Dele

Ololade Bakare

Ify

Kweme

Taiwo & Kehinde Solagbade

Segun

Mr David Olayiwola

Mr David Alabi

PPF Zion International

OlasGlam International

Razor

Mr Obinna

Mr Dele Bakare (VOB International)

Tawio Bakare

Kehinde Bakare

Hannah Bakare

Mrs Doyin Adeyemi

Shade Daniel

Mr Seyi United States

Toxan Global Enterprises Prison

Adeleke Otejo

Favour

Yetty Mama

Loko Tobi Jeannette

MOSES OLUWATOSIN OKIKIADE

Moses Okikiade

(Provenience Enterprise)

We also acknowledge the numerous businesses and private supporters whose names may not be individually mentioned but whose contributions were instrumental in achieving this success.

Your generosity made freedom possible.

A CALL TO ACTION

Hope Beyond the Walls is not a one-time event. It is a movement.

There are still many deserving inmates waiting for a second chance individuals who simply need financial assistance, legal support, and advocacy to reunite with their families and rebuild their lives.

The Association of Models is therefore calling on:

Corporate organizations

Local and international sponsors

Philanthropists

Faith-based organizations

Community leaders

Individuals with a heart for impact

to partner with us.

Our vision is clear:

To secure the release of inmates regularly monthly, quarterly, or during special intervention periods through structured support and transparent collaboration.

HOW TO SUPPORT

Interested partners and supporters can reach out via

Social Media: Official Handles Hope In Motion

Donations and sponsorship inquiries are welcome.

Together, we can turn difficult stories into testimonies of restoration.

ABOUT AOMNGO

The Association of Models (AOMNGO) is a humanitarian driven organization committed to advocacy, empowerment, and social impact. Through projects like Hope Beyond the Walls, the organization works tirelessly to restore dignity and create opportunities for individuals seeking a second chance.

“When we come together, walls fall and hope rises.”

For media interviews, partnerships, and sponsorship discussions, please contact the Association of Models directly.

society

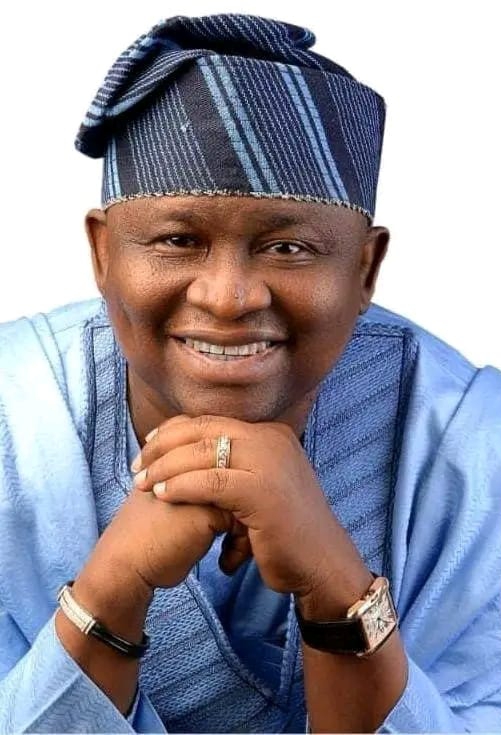

SENATOR ADEOLA YAYI REGISTERS 4000 JAMB CANDIDATES

SENATOR ADEOLA YAYI REGISTERS 4000 JAMB CANDIDATES

In continuation of his educational support initiatives and following established tradition, Senator Solomon Adeola (APC,Ogun West) has successfully paid for and enrolled 4000 indigent students for the 2026 Joint Admission Matriculation Board(JAMB) examination.

According to a release e-signed and made available to members of the League of Yewa-Awori Media Practitioners (LOYAMP) by High Chief Kayode Odunaro, Media Adviser to Senator Adeola and shared with (your mediu), the programme financed by the senator under the “SEN YAYI FREE JAMB 2026” ended on Saturday , February 21, 2026, with a total of 4000 candidates successfully enrolled with their PINs provided.

Commenting on the success of the programme, Senator Adeola said the programme is another leg of his personal educational empowerment for indigent but brilliant citizens preparatory to his scholarship and bursary facilitation for tertiary education institutions’ students.

“As far as I can help it, none of our children will miss educational opportunities arising out of adverse economic predicament of their parents or guardians”, he stated.

Successful candidates cut across all the three senatorial districts of Ogun State with 2183 coming from Ogun West, 1358 coming from Ogun Central and 418 from Ogun East.

Some of the candidates that applied and are yet to get their PINs due wrong information supplied in their profiles and being underage as discovered by JAMB and other reasons are being further assisted to see the possibility of getting their PINs.

The Free JAMB programme of the Senator that has been running for years is well received by appreciative beneficiaries and their parents.

Alhaji Suara Adeyemi from Ipokia Local Government whose daughter successfully got her PIN in the programme said the Senator’s gesture was a welcome financial relief for his family at this period after payment of numerous school fees of other siblings of the beneficiary seeking admission to higher institution.

Also posting on the social media handle of the Senator, a beneficiary Mr. Henry Olaitan, from Odeda LGA said that he would have missed doing the entry examination as his guardian cannot afford the fees for himself and two of his children.

society

House Committee Seeks Stronger Financial Backing for Federal Character Commission

House Committee Seeks Stronger Financial Backing for Federal Character Commission

The Executive Chairman of the Federal Character Commission (FCC), Honorable Hulayat Motunrayo Omidiran, has reassured the commitment of her new leadership to reposition the Commission and strengthen enforcement of the federal character principle, despite prevailing funding challenges.

Hon. Omidiran made this known during the Commission’s budget defence before the House of Representatives Committee on Federal Character at the National Assembly on Friday, February 19, 2026.

The Executive Chairman opened up on inadequate funding has continued to constrain the Commission’s statutory activities, including nationwide monitoring, compliance audits and enforcement measures across Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs).

“We are focused and determined to do the work that the Constitution and the President have entrusted us with,” Omidiran stated.

The FCC Boss, however, assured lawmakers that the Commission remains resolute in ensuring equity, fairness and balanced representation in line with its constitutional mandate.

“As a Commission, it is our responsibility to engage with relevant government parastatals and ministries to secure the necessary funding we require. We believe that with consultation and collaboration, it will be a successful venture for the Commission.”

Earlier, the Chairman of the House Committee on Federal Character, RT. Hon. Ahmed Idris Wase, expressed deep concern over what he described as near-zero budgetary allocation to the Commission, stressing that such financial inadequacies severely undermine its operational effectiveness.

The Plateau State lawmaker assured the Commission of the Committee’s firm legislative backing in advocating for improved funding and strengthening the Commission’s capacity to fully exercise its constitutional mandate.

“We cannot reasonably expect the Federal Character Commission to enforce compliance across Ministries, Departments, and Agencies while grappling with insufficient funding,” Hon. Wase remarked.

“If we are genuinely committed to fairness, equity, and national cohesion, then we must be deliberate in adequately funding the institution established to safeguard these principles.

“As a Committee, we shall work closely with the leadership of the Commission to ensure that its budgetary provisions reflect the magnitude of its mandate. The era of skeletal or token funding must give way to realistic and sustainable financial support,” he concluded.

The budget defence session concluded on a note of renewed collaboration between the House of Representatives and the Commission, reflecting a shared determination to strengthen institutional capacity, enhance accountability, and promote equitable representation within Nigeria’s public service.

SIGNED:

Ademola Lawrence

Spokesperson,

Federal Character Commission

February 20, 2026

-

celebrity radar - gossips6 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips6 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

society5 months ago

society5 months agoReligion: Africa’s Oldest Weapon of Enslavement and the Forgotten Truth

-

news6 months ago

news6 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING

You must be logged in to post a comment Login