society

Matawalle Delivers President Tinubu’s Message to Nigerian Troops in Zamfa

Matawalle Delivers President Tinubu’s Message to Nigerian Troops in Zamfara

…Vows to End Remnants of Bandits in Northwest

The Honourable Minister of State for Defence, Dr. Bello Muhammed Matawalle, has delivered a strong message from President Bola Ahmed Tinubu to troops of Operation FANSAN YAMMA at the North-West Theatre Command Headquarters in Gusau, Zamfara State, charging them to completely eliminate the remaining remnants of bandits terrorising the region.

Speaking on Friday shortly after observing Juma’at prayers at the Command Mosque, Dr. Matawalle conveyed President Tinubu’s deep appreciation for the troops’ patriotism, courage, and remarkable successes in decimating bandit formations across the Northwest.

“Mr. President specifically asked me to tell you that you have done exceedingly well,” he said.

“Most of the key bandit leaders and their foot soldiers have been neutralised through your gallant effort.

“What remains now are a few scattered elements, and the Commander-in-Chief has directed that these remnants must be wiped out completely.

“He assures you of every necessary support — logistics, equipment, welfare, and morale — to finish the job.”

Dr. Matawalle, who was received on arrival by the Theatre Commander, Major-General Warrah Bello Idris, praised the troops for their resilience and professionalism, describing their sacrifices as the bedrock of the gradual return of peace to Zamfara and neighbouring states.

He reiterated the Federal Government’s commitment to providing all required resources, including enhanced welfare packages, modern platforms, and real-time intelligence, to sustain the momentum of the counter-insurgency campaign.

The Theatre Commander, Major-General Idris, welcomed the ministerial visit as a morale booster and a clear demonstration of President Tinubu’s personal interest in the welfare and operational success of troops in the Northwest.

During an operational briefing, the Minister was updated on recent successes, including the neutralisation of high-value targets and the reclamation of several communities previously under bandit control.

In a direct address to hundreds of officers and soldiers drawn up on the parade ground, Dr. Matawalle charged them to remain vigilant, disciplined, and focused, stressing that total victory over banditry in the Northwest is now within reach.

“Your sacrifices will never be in vain. The President is proud of you, the nation is proud of you, and very soon, the people of this region will sleep with their two eyes closed,” he declared.

With the dry season operations intensifying, security analysts believe the renewed presidential backing and ministerial reassurance will galvanise troops towards delivering a decisive blow that will finally end the decade-long banditry scourge in Nigeria’s Northwest.

society

JUSTIFICATIONS FOR IGBO PRESIDENCY

JUSTIFICATIONS FOR IGBO PRESIDENCY

The Igbos, as a people, have been the original occupants of the areas they have inhabited even before colonization and the amalgamation of the various ethnic nationalities that now constitute the geographical entity called Nigeria — a British colonialist brainchild.

In keeping with their natural instinct of improving their environment, the Igbos have contributed immensely to the progressive development of Nigeria in all spheres of human endeavour, ranging from agriculture, commerce, industry, education, health, to sports and other social activities.

The Igbos are naturally hospitable people. They relate to individuals from other ethnic groups as brothers and sisters, even when living outside their ancestral homeland. In many cases, they give their children born outside Igbo land names from their host communities. For instance, there was a Yoruba-named footballer, Okoye, who played for a football club in Northern Nigeria. Many Igbo students born in Western Nigeria bear Yoruba names. Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe’s first four children, born in Lagos, were given Yoruba names such as Abiodun.

It is also on record that Igbos marry widely within their host communities. Igbo women, likewise, marry men from other ethnic groups. The Igbos are known for inter-tribal marriages more than any other ethnic group in Nigeria. Many offspring of these inter-ethnic unions have become prominent sons and daughters of Nigeria, with national and international recognition.

In commerce, beyond importation and exportation, the Igbos are leaders in internal trade, dealing in a wide variety of commodities. There is virtually no part of Nigeria where Igbos are not found engaging lawfully in one form of trade or another. Commercial activity is part and parcel of Igbo life.

Consequently, Igbos are found in every nook and cranny of Nigerian towns, engaging in legitimate means of livelihood — as mechanics, tailors, plumbers, carpenters, household repairers, artisans, and builders of structures ranging from modest homes to large edifices. They are dependable and resourceful when called upon.

At higher professional levels, the Igbos are equally present and distinguished. They are versatile, adaptable, and innovative. One unique characteristic of the Igbo people is that they are independent by nature, yet deeply interdependent. This explains why the Igbos are naturally republican in outlook.

They believe in healthy competition and constantly strive to excel in any career they choose to pursue. As a result, the Igbos have produced not only men and materials but also individuals of exceptional character, resilience, and capacity — men and women of timber and calibre.

(Apologies to Dr. K. O. Mbadigwe, of blessed memory.)

In sporting activities, Igbo sons and daughters have consistently placed Nigeria on the global map. Dick Tiger became a world-renowned figure by winning the World Middleweight and Light Heavyweight Boxing Championships, bringing international recognition to Nigeria. Emmanuel Ifeanyi Okala and other Igbo athletes contributed immensely to Nigeria’s early sporting dominance, while Emmanuel Ifeanyi Juma won Nigeria’s first gold medal at the Commonwealth Games in London.

In football, Dan Anyiam and Onye Wuna were part of the pioneering team that produced Nigeria’s first set of professional footballers. Nwankwo Kanu captained the Nigerian Olympic football team to historic gold at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Christian Chukwu led Nigeria to its first Africa Cup of Nations victory as team captain. Chioma Ajunwa made history by winning Nigeria’s first Olympic gold medal in athletics. Power Mike Okpala also etched Nigeria’s name in global sports history by winning the World Heavyweight Wrestling Championship.

In the early 1960s, shortly after Nigeria’s independence from Britain, an Igbo political leader of exceptional vision, Dr. Michael Okpara, then Premier of the Eastern Region of Nigeria, demonstrated remarkable foresight in industrial development. Following a world economic tour, Dr. Okpara sought federal approval to secure a loan of £50 million sterling for the establishment of a steel complex in Eastern Nigeria.

The proposed steel industry was strategically planned, with raw materials to be sourced from Plateau State, where iron ore and tin were abundant. However, the federal government declined approval, acting on advice allegedly influenced by foreign interests whose steel industries were operating at a loss and feared competition from a Nigerian steel industry within the Commonwealth and African markets.

Ironically, during the civil war, the same federal government that rejected the steel project on economic grounds later approached the former Soviet Union to establish a steel industry. Instead of locating it in the East as originally planned, the project was fragmented into three locations: Ajaokuta in the North, Osogbo in the West, and Aladja in the then Mid-West Region.

This decision not only altered the original vision but also deprived Eastern Nigeria of an industrial foundation that could have accelerated its economic development. It stands as another example of missed opportunities and structural imbalance in Nigeria’s developmental history.

The fact that initiated the proposal was eventually excluded from its execution. This exclusion occurred during the political crisis of 1964–1965, which later escalated into the Nigerian Civil War of 1967–1970. These developments further entrenched structural decisions that marginalized the Eastern Region in critical national projects.

A relevant historical parallel can be drawn from Britain’s experience in managing its steel industry. A British national, who was then heading the Canadian steel industry, had successfully turned it into a prosperous enterprise. Recognizing his exceptional managerial competence, the British government sought his return to manage its own ailing steel industry.

It is on record that Britain paid the sum of £2 million sterling to the Canadian steel industry as compensation to secure the release of this technocrat, Mr. John McGregor, so he could assume leadership of the British steel industry. Under his leadership, the British steel industry broke even in less than five months and soon began making substantial profits.

The transferred steel technology, expertise, and managerial competence became the turning point for the revival of the British steel industry. This example underscores the importance of visionary leadership, technical competence, and deliberate investment in national industrial capacity—qualities that were present in the original Igbo-led steel proposal but were unfortunately disregarded at the time.

This deliberate sidelining of well-conceived initiatives further illustrates how political considerations often overrode economic logic in Nigeria’s developmental trajectory, particularly when such initiatives originated from the Eastern Region.The transfer fee was cost-effective.

After the civil war, the Nigerian government engaged one of the deputies from the Canadian steel industry, Dr. Eze Melari, to aid in the construction of Ajaokuta Steel Company and its associated subsidiaries. Dr. Melari, alongside Russian engineers, worked harmoniously and completed up to 90% of the project when General Buhari overthrew Shagari and assumed power as another military dictator.

Buhari’s first act was not only to remove the highly qualified Igbo technocrat, Dr. Eze Melari — who had earned his PhD in 1957 and had more than 24 years of working experience abroad — but to replace him with an engineer, Arthur, who held only a BSc, obtained in 1977, twenty years after Dr. Melari had earned his doctorate in the same discipline.

Is it any wonder, then, that the Nigerian steel industry has produced many billionaires but not a single sheet of steel? Had this industry been established at the time envisioned by the foresighted initiator, the cost of investment would have been lower, employment would have been generated, foreign exchange earnings increased, and tin and iron ore mines would have flourished. Instead, short-sighted leadership deprived Nigeria of a critical economic breakthrough.

What can one expect from a policy that moves “one step forward and twenty steps backward,” driven by economic illiteracy and shallow-mindedness? The failure of the steel industry is symptomatic of a broader cycle of mismanagement and negligence — a kind of national “karma” that persists until Nigeria confronts the structural mistakes of its past.

It is important to note that the victims of this mismanagement were the Eastern Nigerian government and its people. Even today, Nigeria is unlikely to complete this project, yet continues to expend trillions in paying workers’ salaries without producing anything tangible. This mirrors the situation with the non-productive oil refineries, which remain a drain on the economy while failing to deliver results.

Political Exclusion: The Cause

Before the civil war, Nigeria practised true federalism. However, since after the war, the country has operated more like a military-styled, constrained federation, where states go to Abuja cap in hand for allocations, and where some states are more favoured than others.

The centre of leadership has been restricted to certain groups, with the particular exclusion of an ethnic group that has the capacity to rescue the nation from its malevolent journey into bottomless economic pits. The result is that our national currency has lost its value, while those of other competing nations continue to appreciate. Our products have become comparatively cheaper, not because of productivity, but due to economic weakness.

The Igbos have, on several occasions, sought to occupy the presidency of Nigeria but have been denied the opportunity, sometimes through pre-emptive manoeuvres. Other ethnic groups have had their turns through democratic, near-democratic, or even undemocratic routes.

It is plain to see that those who do everything to rule are often more concerned with what they can take from office rather than what they can offer. If a Nigerian president is officially paid about one million five hundred thousand naira monthly, or eighteen million naira per annum—amounting to seventy-two million naira for a four-year tenure—how then can one justify the payment of one hundred million naira for nomination and expression-of-interest forms? (Courtesy of All Progressives Congress nomination and expression fees.)

It is only in Nigeria that such practices exist, where politics has become a lucrative business for opportunists and political merchants. It is therefore high time that a Nigerian of Igbo extraction is given the opportunity to lead Nigeria.

Fortunately, there are many individuals of Igbo extraction with the capability, human efficiency, and patriotic interest to prove that Nigeria’s problems—though man-made—are difficult but not impossible or insurmountable. Some of them have already demonstrated their competence at lower levels, thereby qualifying them for even greater responsibilities at higher mandates.

Second tenure in any elective office is neither automatic nor a right. It is dependent solely on performance during the first tenure. A failed performer is eliminated—root and branch. The principle of checks and balances is always appropriate in this regard.

The American federal constitution stipulates a maximum of two tenures for a president. However, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was elected during the Great Depression, was allowed to contest the presidential election for four successive terms. Towards the end of his second tenure, the United States Congress voluntarily lifted the law that limited presidents to a maximum of two terms, enabling him to contest for a third term, which he won overwhelmingly. This resolution was again repeated towards the end of his third tenure, qualifying him to contest and win a fourth term, during which he died on April 12, 1945.

The unique aspect of this historic exception is that the motion was not moved by members of the president’s party. The resolution, in essence, stated: “In view of your efficiency and contribution to the economic stability of the nation, Congress hereby lifts the stipulated two-term limit to enable you to contest for another term. This resolution remains valid as long as you remain in office.” No other American president has ever been so honoured.

To further demonstrate that the Igbos deserve to hold the office of President of Nigeria, below is a list of the occupants of the office of Head of Government and Head of State since Nigeria’s independence in 1960. Notwithstanding that the office of Prime Minister began in 1957 and was held by the same individual until 1966, the records are as follows:

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (1957–1966) – North-East

General J.T.U. Aguiyi-Ironsi (1966 – six months) – South-East

General Yakubu Gowon (1966–1975) – North-Central

General Murtala Mohammed (1975–1976) – North-West

General Olusegun Obasanjo (1976–1979) – South-West

Alhaji Shehu Shagari (1979–1983) – North-West

General Muhammadu Buhari (1983–1985) – North-West

General Ibrahim Babangida (1985–1993) – North-Central

Chief Ernest Shonekan (August–November 1993) – South-West

General Sani Abacha (1993–1998) – North-West

General Abdulsalami Abubakar (1998–1999) – North-Central

Chief Olusegun Obasanjo (1999–2007) – South-West

Umaru Musa Yar’Adua (2007–2010) – North-West

Goodluck Jonathan (2010–2015) – South-South

Bola Ahmed Tinubu (2015–date) – South-West

From the above, it is clear that the South-East is long overdue for the presidency. Equity demands fairness. When one approach has consistently failed to produce balance, wisdom requires a shift to avoid injustice. All equals must be treated equally.

The Igbos are naturally gifted with men who can make things happen—men imbued with the capacity, intellect, and material understanding required to effect positive change. It is time to give them a chance to do what the Nigerian political “Napoleons” could not do, rather than continually allowing mouth-watering, economically selfish political machineries whose stock-in-trade is the engagement in reckless investments and the diversion of public resources for infinitesimal returns on huge sums invested.

Like the infamous Dr. Joseph Goebbels of the German Nazi Party, some individuals daily dish out white lies in the name of propaganda, erroneously believing they have convinced the people, forgetting that the best brains in the country have largely been outside government since 1970. The criteria for appointments into government have been largely based on ethnicity, religion, kinship, party affiliation, or political compensation. Merit has been completely sidelined and rendered a non-factor.

Added to this is the indomitable and pervasive culture of corruption, which remains the major ulterior motive behind the quest for public office. This singular factor largely explains why Nigeria is where it is today. These traits, however, can be overcome by those who genuinely desire to serve and make a lasting name through selfless service to the nation, rather than by cabals of greedy looters whose past records are unencouraging, yet who continue to seek and be granted mandates to rule—thereby mortgaging the future of over 200 million unfortunate citizens and generations yet unborn.

It is therefore justifiable—morally, politically, and equitably—to give the hitherto marginalized South-East a chance to clean up the politically, economically, and security-wise messed-up table. Cleaning this table politically, economically, and above all addressing the current state of insecurity, though an uphill task, is not insurmountable. This has been demonstrated in the past at the state level during difficult periods.

The interest and welfare of Nigeria must always supersede the interest and welfare of any particular section of the country.

SIGNED

HON. PRINCE CHINEDU NSOFOR(KPAKPANDO NDIGBO) NATIONAL COORDINATOR IGBO PRESIDENCY PROJECT AND FOUNDING PRESIDENT IGBO HEROES AND ICONS FOUNDATION

society

Trump Raises Alarm Over Iran’s Expanding Missile Arsenal Amid Escalating Middle East Tensions

Trump Raises Alarm Over Iran’s Expanding Missile Arsenal Amid Escalating Middle East Tensions

By George Omagbemi Sylvester | Published by SaharaWeeklyNG

“U.S. president claims Tehran had more missiles than expected and was weeks away from launching attacks, sparking renewed global security concerns.”

United States President Donald Trump has intensified global debate over the growing crisis in the Middle East after claiming that Iran possesses significantly more missiles than American intelligence initially estimated and was allegedly preparing an imminent attack against U.S. interests. Trump made the assertion while commenting on the escalating tensions between Washington and Tehran, warning that Iranian military capabilities were far greater than previously understood.

Trump argued that new intelligence assessments revealed that Iran had rapidly expanded its ballistic missile stockpile and had developed the capacity to strike American forces and regional allies with little warning. According to him, Iranian military planners were “within a week” of launching coordinated attacks before preventive military measures were taken. The remarks have reignited international discussions about the scale of Iran’s missile program and the broader security implications for the Middle East.

The claims emerged amid renewed tensions between the United States and Iran following military operations targeting Iranian facilities believed to be linked to weapons development and regional military coordination. Washington has maintained that such actions were necessary to prevent a potential escalation and to protect American personnel stationed across the region.

Security analysts, however, caution that the situation reflects a deeper geopolitical rivalry rather than a single imminent threat. Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman, a renowned military analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, noted that Iran’s missile development has been expanding steadily for years as part of its broader deterrence strategy. According to Cordesman, “Iran relies heavily on missile capabilities because it cannot match the conventional military power of the United States or its regional partners. These weapons are central to its defensive posture and influence across the region.”

Similarly, Professor Vali Nasr, a Middle East expert at Johns Hopkins University, argued that the missile issue must be viewed within the wider strategic competition between Iran and Western powers. Nasr explained that “Iran’s missile program has long been a tool of strategic leverage. While it certainly raises legitimate security concerns, the rhetoric surrounding it often reflects political positioning as much as intelligence assessments.”

Iran has consistently maintained that its missile program is purely defensive and aimed at safeguarding its sovereignty against foreign intervention. Officials in Tehran have repeatedly denied planning any direct attacks on the United States, insisting that their military capabilities are intended to deter aggression rather than provoke conflict.

Despite these denials, regional tensions remain high. Analysts warn that heightened rhetoric from political leaders, combined with military deployments and intelligence claims, could fuel misunderstandings that might spiral into a broader confrontation.

Energy markets and global security observers are also closely monitoring the situation because instability in the Middle East (one of the world’s most critical energy corridors) can have far-reaching economic consequences. Economist Paul Krugman emphasized that geopolitical shocks in the region often reverberate through global markets. “Any serious escalation involving Iran can disrupt oil supply expectations, unsettle financial markets and affect economic stability far beyond the region,” he said.

Diplomatic experts say sustained dialogue remains the most viable path to preventing further escalation. Former U.S. diplomat Ryan Crocker stressed that “military pressure alone rarely resolves deeply rooted geopolitical disputes. Long-term stability requires negotiations, trust-building measures and regional cooperation.”

As the standoff continues, governments, security institutions and international observers remain alert to developments that could reshape the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East. Trump’s comments have added another layer of tension to an already volatile environment, reinforcing fears that the region could face renewed instability if diplomatic efforts fail to gain traction.

While policymakers debate the scale of the threat posed by Iran’s missile arsenal, experts agree that the stakes remain extremely high; not only for the United States and Iran but also for the broader international community seeking to prevent another major conflict in the Middle East.

society

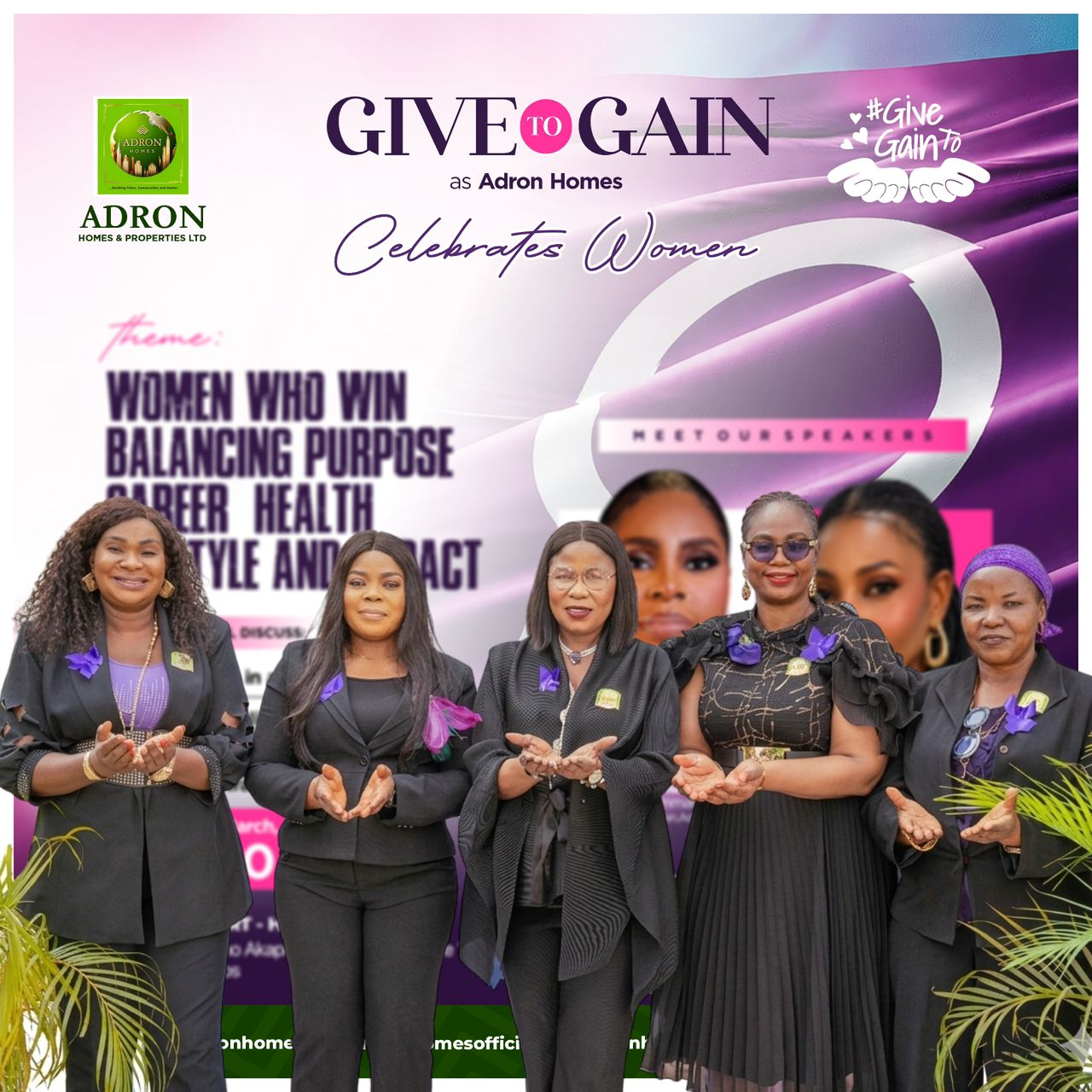

Empowered Women, Stronger Nation: Building Futures Through Property Ownership

Empowered Women, Stronger Nation: Building Futures Through Property Ownership

As the world commemorates International Women’s Day, attention rightly turns to the extraordinary role women play in shaping families, communities, and national economies. Beyond nurturing homes and leading in boardrooms, women are increasingly emerging as powerful drivers of nation-building through one of the most transformative assets of all, property ownership.

Across Nigeria, women are steadily breaking long-standing barriers in business, governance, technology, education, and entrepreneurship. Their expanding economic influence is uplifting households, strengthening institutions, and reinforcing the nation’s financial foundation. The evidence is clear: when women earn, communities prosper; when women invest, societies advance.

One of the most visible expressions of this progress is in real estate acquisition. Property ownership empowers women with security, stability, and the ability to build generational wealth. A home is more than a structure of concrete and steel, it is a platform for legacy, enterprise, social mobility, and long-term influence.

From young professionals purchasing their first plots of land to seasoned executives expanding diversified investment portfolios, Nigerian women are redefining wealth creation and strategic future planning. Their growing presence in the property market signals a cultural and economic shift toward asset-backed empowerment.

Real estate remains one of the safest and most rewarding investment paths, and women are embracing the opportunity with confidence. Their participation is reshaping urban development patterns, influencing housing demand, and stimulating construction, infrastructure growth, and employment value chains nationwide.

At Adron Homes and Properties, empowering women through property ownership is seen as a direct investment in national progress. Every woman who secures land or a home strengthens family stability, fuels economic growth, and inspires future generations to dream bigger and aim higher.

This International Women’s Day, women are celebrated not only for who they are, but for what they build:

* Builders of families

* Drivers of economic growth

* Investors in the future

* Architects of generational wealth

To honor their impact, Adron Homes is expanding access to ownership through flexible payment plans, inclusive investment opportunities, and customer-friendly support services designed to make property acquisition simple, transparent, and rewarding.

Because when women rise, nations thrive. And when women own property, the future is secured.

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoReligion: Africa’s Oldest Weapon of Enslavement and the Forgotten Truth

-

news3 months ago

news3 months agoWHO REALLY OWNS MONIEPOINT? The $290 Million Deal That Sold Nigeria’s Top Fintech to Foreign Interests

-

Business6 months ago

Business6 months agoGTCO increases GTBank’s Paid-Up Capital to ₦504 Billion

-

society6 months ago

society6 months ago“You Are Never Without Help” – Pastor Gebhardt Berndt Inspires Hope Through Empower Church (Video)