society

Truth Under Fire: Bishop Matthew Kukah’s Clarification on Christian Persecution in Nigeria from Context, Controversy and Consequences. By George Omagbemi Sylvester

Truth Under Fire: Bishop Matthew Kukah’s Clarification on Christian Persecution in Nigeria from Context, Controversy and Consequences.

By George Omagbemi Sylvester

“How misrepresentation, insecurity and national debate collided around one of Nigeria’s most respected moral voices and what it reveals about the country’s struggle with violence, religious harmony and truth.”

In a nation grappling with deep insecurity, sectarian violence and rising global scrutiny, one of Nigeria’s most prominent clerics (Most Rev. Matthew Hassan Kukah) has found himself at the eye of a media storm. Reports circulating in recent weeks claimed that Bishop Kukah “MADE A U-TURN” and denied that Christians are persecuted in Nigeria. These claims gained rapid traction online and triggered widespread public emotion, frustration and critique within Christian communities at home and among the diaspora. But the story (when examined closely, thoroughly and with context) reveals both serious misreporting and the larger fault lines in Nigeria’s national discourse on security and religious freedom.

In reality, Bishop Kukah unequivocally denied ever saying Christians are not persecuted in Nigeria. Far from dismissing the suffering of religious communities, he argued against simplistic labels like “GENOCIDE” or selective narratives that detract from deeper causes of insecurity and called for unity, accountability and disciplined civil engagement. His clarification, issued directly from his own statement and multiple reliable media reports, must be understood in full.

The Mischaracterisation and Kukah’s Response. The controversy stems from remarks the Bishop made in various settings, including at the launch of the Aid to the Church in Need’s World Report on Religious Freedom at the Vatican and at a Catholic convention in Kaduna. Some media outlets selectively quoted him questioning widely circulated figures (including claims that 1,200 churches are burned each year) and suggesting that no one had accurately engaged the Catholic Church on these numbers. This was portrayed by critics as a denial of Christian persecution.

Bishop Kukah responded with a formal clarification, titled “Of the Persecution of Christians in Nigeria: My Response,” where he stated he was “BAFFLED” that despite the clarity of his position, people continued to attach to him a claim that he said Christians were not persecuted. “Nothing could be further from the truth,” he insisted. He explained that his remarks were mischaracterised and taken out of context.

Kukah emphasised that his comments were about disagreements over language and labels (such as the difference between persecution, genocide and systemic violence) and that calling for precision in language does not equate to dismissing the reality of suffering. Across all his speeches, he has consistently recognised the ongoing attacks, killings, abductions and church burnings impacting Nigerian communities.

Laying Out the Context: Nigeria’s Insecurity Crisis. To understand why this debate matters so deeply, it is important to situate Bishop Kukah’s comments within the broader reality of Nigeria’s insecurity. Over the last decade, Nigeria has endured attacks from extremist groups, bandits, militant herders and other armed actors that have disproportionately affected rural and religious communities. Many international policy analysts have argued that these attacks (particularly in the Middle Belt and northern regions) carry clear patterns of targeting minority populations, including Christians.

For example, testimony before the United States House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee highlighted how militant extremist outfits and organised armed groups have attacked farming communities (with many victims identifying as Christians) and have displaced millions. These attacks often push populations off ancestral lands, fuel humanitarian crises and disrupt civic life across ethnic and religious communities.

Groups such as Open Doors, a respected international research body on religious freedom, have consistently reported that Nigeria ranks among the world’s most dangerous countries for Christians due to targeted violence linked to extremist and insurgent activity.

Yet, Nigerian governing authorities (including Abuja’s leadership) have repeatedly criticised the use of terms like “GENOCIDE” or “RELIGIOUS PERSECUTION” as oversimplified or politically motivated, insisting that insecurity affects all citizens irrespective of faith. These official positions have contributed to passionate debates about how best to describe and respond to violence.

Why Language Matters: PERSECUTION vs. GENOCIDE. One core aspect of Bishop Kukah’s message is his insistence on accurate language as foundational for moral clarity and constructive policy responses. Contrary to claims that he denies persecution, Kukah’s argument is that terms like “GENOCIDE” have specific legal and philosophical definitions (requiring proof of intent to eliminate a group) which cannot be loosely applied without robust evidence.

“Killing 10 million people still does not amount to genocide, if the intention to eliminate a group is absent,” he said, emphasising the need for careful, disciplined discourse rather than inflammatory rhetoric.

This distinction is not trivial. In international law, as defined under the GENOCIDE CONVENTION, genocide is a specific crime that requires intent to destroy a national, religious or ethnic group in whole or in part. Misuse of such terms can distort public understanding and impede accurate reporting, advocacy and diplomacy. Bishop Kukah’s point (misunderstood by many) reflects this complexity and insists that serious claims require serious evidence.

Uproar and Backlash: Public Reaction vs. Intent. The misreporting sparked intense criticism from Christian advocacy groups and ordinary Nigerians, with many accusing Kukah of abandoning moral leadership or aligning with political power. Social media conversations multiplied allegations that the Bishop had “LOST HIS MORAL COMPASS” by questioning narratives of persecution, with some voices resorting to personal attacks rather than constructive debate.

These reactions, while emotionally powerful, often overlook two critical points: First, the Bishop has repeatedly affirmed the existence of violence against Christians; and second, he has urged unity not division, within and between faith communities. His clarification stressed that trauma and suffering must not be dismissed by debates over terminology, but that precision allows solutions to be targeted and sustainable.

Scholarly and Expert Perspectives. Experts in religious freedom and conflict analysis have noted that Nigeria’s situation defies simplistic categorisation. Dr. Nina Shea, a leading expert on religious liberty, has testified before international bodies on how Nigeria’s violence involves layers of pastoralist-farmer conflict, jihadist terrorism and weak state responses, all intersecting with religious identities.

Shea and others have pointed out that systematic violence against Christian communities often stems from the failure of the Nigerian state to protect vulnerable populations and the activities of militant groups that exploit ethnic and religious fault lines. These perspectives align with Bishop Kukah’s broader concern about insecurity, even if they differ on how to label the violence.

Beyond legal definitions, respected theologians argue that speaking about persecution has spiritual and moral weight. Theologian Miroslav Volf wrote that “truth without compassion, like compassion without truth, does not save us” though highlighting the need for accurate understanding and empathetic responses to human suffering.

What This Means for Nigerians and the World. At stake in this debate is more than a semantic argument. It is a reflection of how Nigeria (one of Africa’s largest democracies and most religiously diverse nations) confronts violence, protects minorities and navigates competing narratives.

Misreporting and sensationalism undermine constructive dialogue. When leaders like Bishop Kukah are misconstrued, the public discourse can quickly polarise, eroding trust and distracting from urgent calls for accountability, reform and effective security policy.

Kukah himself has emphasised that Nigerians must transcend victimhood to demand transformations in governance, civic culture and national identity. True leadership, in his reckoning, arises not from political grandstanding but from disciplined, honest appraisal of challenges and collective action towards peace, a message resonating far beyond Nigeria’s borders.

A Parting Thought.

The controversy over Bishop Matthew Kukah’s remarks on Christian persecution in Nigeria reveals deeper truths about the country’s struggle with insecurity, identity and public discourse. While misinterpretations sparked justified emotional responses, a careful look at Kukah’s own statements shows an unwavering recognition of suffering and a call for unity, accurate language and collective responsibility.

In a world where violence against religious communities is both a local tragedy and a global concern, leaders must be judged not by headlines but by the full context of their words and the integrity of their intentions. Nigeria’s future depends on clarity, courage and commitment to justice; principles Bishop Kukah has articulated, even amid misunderstanding.

society

Stop Means Stop”: Legal Experts Warn Ignoring ‘Stop’ During Intimate Acts Can Be Criminally Punishable

“Stop Means Stop”: Legal Experts Warn Ignoring ‘Stop’ During Intimate Acts Can Be Criminally Punishable

By George Omagbemi Sylvester | Published by SaharaWeeklyNG

“Grounded in international law and consent principles, legal authorities stress that continuing sexual activity after a partner withdraws consent may constitute sexual assault and lead to imprisonment.”

A growing body of legal interpretation and expert opinion reaffirm that consent in intimate encounters is not a one-off event but an ongoing requirement; withdrawn at any time by either participant. Legal practitioners and rights advocates are increasingly warning that if one partner clearly says “stop” during sexual activity and the other continues, this conduct can constitute a criminal offence with significant penalties, including imprisonment.

Consent must be “a voluntary agreement to engage in the sexual activity in question,” and crucially can be revoked at any stage. Once a partner expresses withdrawal of consent (by words like “stop” or by unmistakable conduct) the other party is legally obligated to cease all activity immediately. Failure to respect this is widely recognised in multiple legal jurisdictions as sexual assault or rape.

Professor Deborah Rhode, a prominent authority on legal ethics, has stated: “Respect for autonomy and bodily integrity lies at the core of consent law. Ignoring a partner’s withdrawal of consent undermines basic personal freedoms and is treated as a serious offence in criminal law.”

According to experts, this legal principle is not limited to strangers but applies equally to long-term partners and spouses. The Criminal Code in many countries explicitly rejects implied or blanket consent based on relationship status.

Human rights lawyer Amal Clooney has similarly emphasised that clear communication and mutual agreement are essential, and that “once consent is withdrawn, any continued sexual activity crosses the line into criminal conduct.”

This means that in places where consent law is well-established, ignoring an explicit “stop” can lead to charges of sexual assault, with courts interpreting such conduct as a violation of an individual’s autonomy and dignity.

The issue has gained media and legal attention in recent years across numerous jurisdictions (including Canada, parts of Europe, and reform discussions in U.S. states) as courts and legislatures clarify that sexual consent is continuous and revocable at any time. Although no globally consolidated database exists of individual cases tied specifically to a news report on this warning, reputable legal frameworks consistently reinforce that continuing after “stop” is unlawful.

The subject engages legal scholars, criminal law practitioners, human rights experts, and statutory bodies advocating sexual violence prevention. Law enforcement agencies and prosecutors may pursue charges when clear evidence shows that consent was withdrawn and ignored.

In practice, consent frameworks require that the person initiating or continuing sexual activity take reasonable steps to ensure ongoing affirmation of willingness. Silence, passive behaviour, or failure to stop when asked cannot substitute for ongoing consent.

In summary, the legal maxim is clear: verbal or unambiguous withdrawal of consent must be respected. Ignoring it shifts the encounter from consensual to criminal, potentially resulting in serious legal consequences including imprisonment.

society

Lagos Family Property Dispute Turns Violent After Death of Omotayo Ojo

Lagos Family Property Dispute Turns Violent After Death of Chief Omotayo Ojo

By Ifeoma Ikem

A festering family dispute over property has escalated into a series of violent attacks in Lagos, leaving residents of a contested apartment in fear for their safety.

Mrs. Omotayo-Ojo-Alolagbe (Nee Omotayo-Ojo) the third child and first daughter of the late Omotayo Ojo, has alleged repeated assaults and destruction of property by her siblings from her father’s other marriages.

According to her account, hostility against her began while her father was still alive, allegedly fueled by the affection and support he showed her. She claimed that tensions worsened after his death in 2019.

Mrs. Alolagbe stated that her late father had given her a particular apartment during his lifetime, assuring her she would not suffer hardship, especially after her husband left the marriage. She said the property became her primary source of livelihood and shelter.

However, she alleged that her siblings had sold off several other family properties and were determined to dispossess her of the apartment allocated to her by their father.

The dispute reportedly turned violent on Nov. 15, 2025, when unknown persons allegedly attacked the building. She said the incident prompted her to petition the Chief Judge of Lagos State and the Commissioner of Police.

Despite the pending legal proceedings, she alleged that another attack occurred on Jan. 21, 2026. During that incident, parts of the building were vandalised, including the walkway and the main gate, which was reportedly removed.

A third attack was said to have taken place on Feb.18, 2026, during which the roof, gates, and sections of the walkway were allegedly dismantled. Residents were reportedly assaulted, and some were allegedly forced to part with money under duress.

Tenants in the apartment complex are said to be living in fear amid the repeated invasions, expressing concern over their safety and uncertainty about further violence.

Mrs. Alolagbe alleged that the attacks were led by a man identified as Mr. Alliu, popularly known as aka “Champion,” whom she described as a political thug. She claimed he arrived with a group of about 50 men, allegedly brandishing weapons and breaking bottles to intimidate residents.

She further alleged that the group boasted of connections with senior police officers, politicians in Lagos State, and even the presidency, claiming they were untouchable.

According to her, some arrests were initially made following the incidents, but the suspects were later released. She expressed concern that the alleged perpetrators continue to threaten her, making it difficult for her to move freely.

She also disclosed that during a meeting on Feb. 23, 2026, an Area Commander reportedly told her that little could be done because the matter was already before a court of law.

The development has raised concerns about the enforcement of law and order in civil disputes that degenerate into violence, particularly when court cases are pending.

As tensions persist, residents and observers are calling on relevant authorities to ensure the safety of lives and properties ,while allowing the courts to determine ownership and bring lasting resolution to the dispute.

society

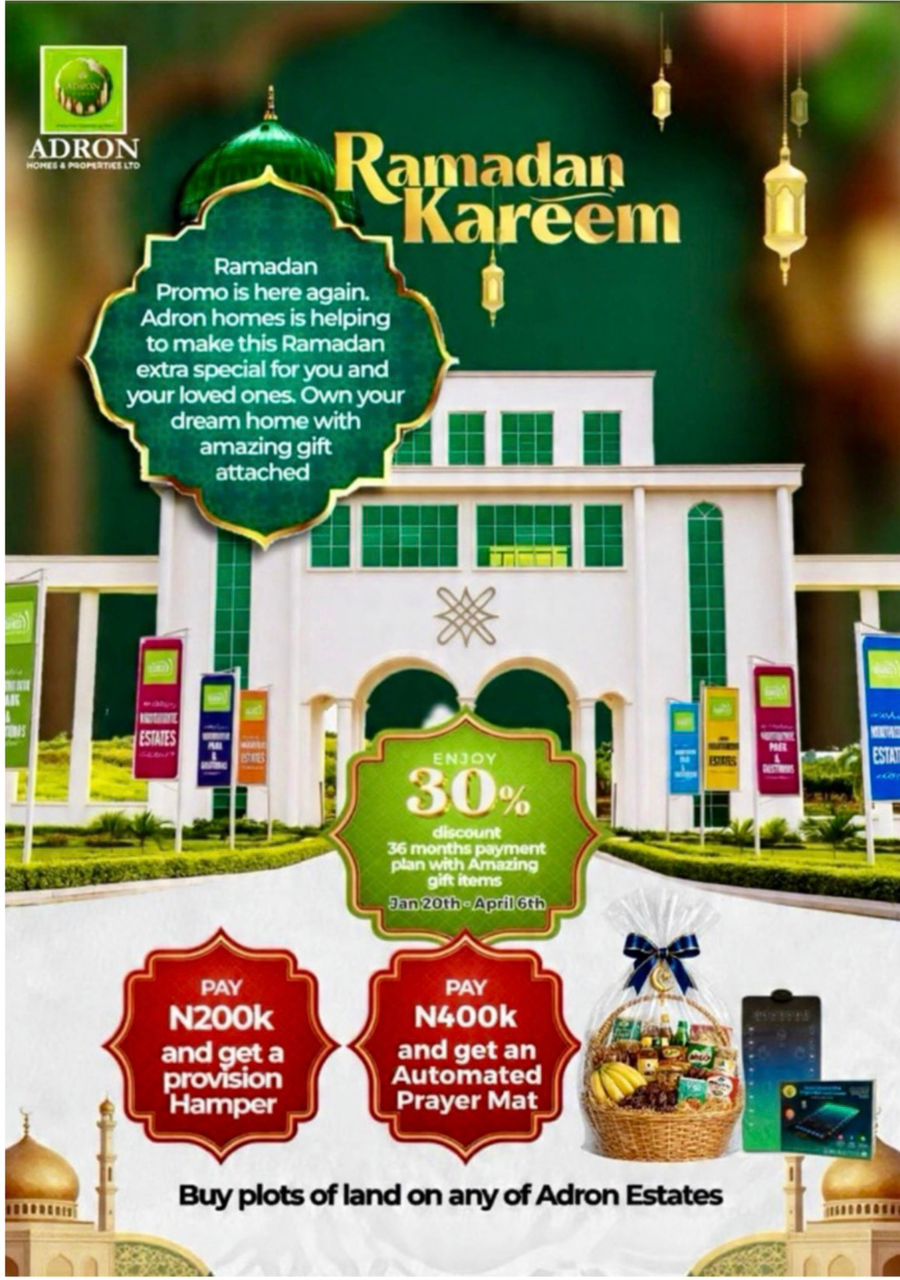

Adron Homes Introduces Special Ramadan Offer with Discounts and Gift Rewards

Adron Homes Introduces Special Ramadan Offer with Discounts and Gift Rewards

As the holy month of Ramadan inspires reflection, sacrifice, and generosity, Adron Homes and Properties Limited has unveiled its special Ramadan Promo, encouraging families, investors, and aspiring homeowners to move beyond seasonal gestures and embrace property ownership as a lasting investment in their future.

The company stated that the Ramadan campaign, running from January 20th to April 6th, 2026, is designed to help Nigerians build long-term value and stability through accessible real estate opportunities. The initiative offers generous discounts, flexible payment structures, and meaningful Ramadan-themed gifts across its estates and housing projects nationwide.

Under the promo structure, clients enjoy a 30% discount on land purchases alongside a convenient 36-month flexible payment plan, making ownership more affordable and stress-free.

In the spirit of the season, the company has also attached thoughtful rewards to qualifying payments. Clients who pay ₦200,000 receive a Provision Hamper to support their household during the fasting period, while those who pay ₦400,000 receive an Automated Prayer Mat to enhance their spiritual experience throughout Ramadan.

According to the company, the Ramadan Promo reflects its commitment to aligning lifestyle, faith, and financial growth, enabling Nigerians at home and in the diaspora to secure appreciating assets while observing a season centered on discipline and forward planning.

Reiterating its dedication to secure land titles, prime locations, and affordable pricing, Adron Homes urged prospective buyers to take advantage of the limited-time Ramadan campaign to build a future grounded in stability, prosperity, and generational wealth.

This promo covers estates located in Lagos, Shimawa, Sagamu, Atan–Ota, Papalanto, Abeokuta, Ibadan, Osun, Ekiti, Abuja, Nasarawa, and Niger states.

As Ramadan calls for purposeful living and wise decisions, Adron Homes is redefining the season, transforming reflection into investment and faith into a lasting legacy.

-

celebrity radar - gossips6 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips6 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society5 months ago

society5 months agoReligion: Africa’s Oldest Weapon of Enslavement and the Forgotten Truth

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

news7 months ago

news7 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING