society

Time is the One Enemy That Cannot Be Bought or Bargained With By Femi Oyewale

Time is the One Enemy That Cannot Be Bought or Bargained With

By Femi Oyewale

We write not as antagonists but as patriots stirred by a profound and urgent alarm for our nation. The headlines that scream from our pages and screens are more than mere news; they are a symphony of distress from a people whose faith in the foundational covenant of governance—their security and welfare—is fraying towards breaking point.

Nigeria’s security crisis is not merely challenging; it is a fabric unravelling in real time. The brazen abduction of our children, the resurgent fury of jihadist factions in the Northeast, and the metastasizing cancer of banditry and communal violence represent the most clear and present danger to the Nigerian ideal since our civil war. With each passing day, trauma deepens, a humanitarian catastrophe widens, and millions of our compatriots are pushed to the grim precipice of hunger and despair.

Your declaration of a nationwide emergency and the bolstering of our security forces were necessary, even commendable, first steps. But the unvarnished truth, Your Excellency, is that the clock is ticking, and time is a luxury you do not have. The velocity of this collapse demands more than declarations; it insists upon a fundamental and immediate strategic rebirth. The Nigerian people are not just watching; they are suffering. And in a true democracy, their welfare—their simple safety—is the sole, non-negotiable measure of a government’s legitimacy.

In this most critical hour, to ignore the nation’s deep bench of battle-hardened, experienced security professionals would be an act of strategic negligence. We speak of leaders like former Chief of Army Staff, Lt. Gen. Tukur Buratai (rtd), who embodies a trifecta of assets we can not afford to leave sidelined: deep operational knowledge, invaluable institutional memory, and the political acumen to navigate a complex war.

Consider what such expertise offers at this precipice:

Operational Wisdom, Not Just Force: This is not about reliving past campaigns but about applying their hard-won lessons. Experts like Buratai possess a nuanced grasp of asymmetric warfare, cross-border coordination, and logistical mastery that can prevent our efforts from being blind, costly, and futile.

A Cohesive Intelligence Architecture: Our enemies feast on our disunity. A seasoned security leader can dismantle bureaucratic inertia to fuse our fractured intelligence efforts—military, police, and civilian—into a single, sharp instrument. This is critical in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin, where threats respect no borders.

The Reform Our Gallant Forces Deserve: Our troops are consistently let down by systemic failures—poor logistics, sapped morale, and fatal intelligence leaks. Who better champion the urgent reforms in training, welfare, and accountability than those who have commanded these institutions from the inside?

Credibility and Critical Coalition-Building: Decisive victory requires buy-in from every tier of governance and from our international partners. A respected former service chief can be the credible intermediary, bridging the dangerous gap between uniformed forces and civilian authority and rallying regional allies with a voice they know and trust.

We are not naive to the risks. The path forward can not be a mere militarization of the state. Any role for such experts must be framed within a broader, non-negotiable commitment to attacking the root causes: poverty, hopelessness, and the cavernous gaps in local governance. Civilian oversight, transparency, and a parallel surge in development and reconciliation are the essential safeguards.

Thus, we propose a pragmatic and urgent middle path:

· Empower Security Experts as Strategic Architects: Integrate them formally as chief advisers and task them with designing a unified, actionable counter-insurgency strategy.

· Fast-Track Intelligence Integration: Mandate the creation of a single, interoperable intelligence framework with a brutally short deadline.

· Pair Security with Sustenance: Every military advance must be accompanied by an immediate, clear plan for humanitarian access, agricultural revival, and community reconciliation.

· Activate Regional Diplomacy with Immediacy: Leverage their networks to secure concrete, actionable cooperation from our neighbours and international partners—now.

Your Excellency, the legacy of your administration, is being written daily in the blood and tears of Nigerians caught in the crossfire. The institutional knowledge possessed by leaders like General Buratai is not a magic wand, but it is a decisive force multiplier we can no longer afford to discard. It is the vital ingredient in a comprehensive strategy that must marry security with governance, development, and dialogue.

The hour is late. The nation’s patience is exhausted. The world is watching. We urge you to act with the historic courage and decisiveness this moment demands. Bring in the experience, empower the knowledgeable, and marry their expertise with an unrelenting focus on the welfare of the people. This is the only way to secure not just the nation’s borders but the very soul of our democracy.

The choice is stark: a legacy of restored security and national gratitude, or a descent into a chaos from which we may not return. For the sake of Nigeria, we pray you choose wisely.

And we pray you choose now.

society

Only Fools Assume They Can Fight the State Like El-Rufai Did

Only Fools Assume They Can Fight the State Like El-Rufai Did — Ope Banwo

Public affairs commentator Ope Banwo has described as “strategic folly” the assumption that a former political office holder can openly confront the Nigerian state without consequences.

Banwo made the remarks while analysing the recent detention of former Kaduna State governor Nasir El-Rufai, which he said underscores the imbalance between individual ambition and institutional power.

“Only fools believe they can challenge the state the way El-Rufai did and continue life as usual,” Banwo stated. “The Nigerian state is not a debating club.”

He noted that El-Rufai repeatedly made grave allegations against government institutions on national platforms, including claims of conspiracies and surveillance, without publicly providing evidence. According to Banwo, such statements, whether true or not, inevitably provoke a response from authorities determined to maintain control.

Banwo explained that when a former official challenges state authority, it is often interpreted not as dissent but as defiance. “The state reacts to defiance, not arguments,” he said.

He further argued that El-Rufai appeared to overestimate his political backing, assuming that his past influence would shield him from institutional action. “That assumption collapsed the moment power called his bluff,” Banwo added.

According to him, the involvement of agencies such as the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission and the Department of State Services illustrates how swiftly the machinery of state can move once a decision is made.

Banwo also highlighted the public’s muted reaction as a crucial lesson. “There were no mass protests. That silence shows the difference between perceived influence and real leverage,” he said.

He stressed that political power in Nigeria is sustained by active control of institutions, not by reputation. “Once you lose the levers, your bravado becomes a liability,” Banwo noted.

He concluded that El-Rufai’s experience should caution other former power brokers against mistaking visibility for authority. “Fighting the state without power is not courage; it is miscalculation,” he said.

society

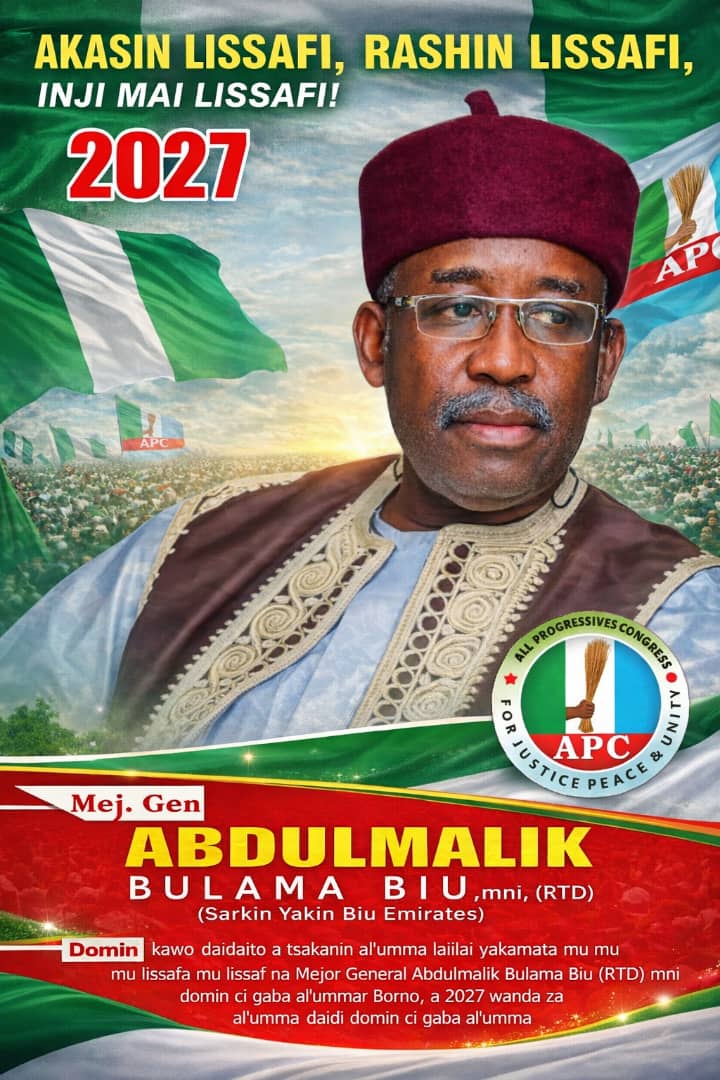

GENERAL BULAMA BIU APPLAUDS SUCCESSFUL APC CONGRESSES, URGES NEW EXECUTIVES TO FOCUS ON GOOD GOVERNANCE

GENERAL BULAMA BIU APPLAUDS SUCCESSFUL APC CONGRESSES, URGES NEW EXECUTIVES TO FOCUS ON GOOD GOVERNANCE

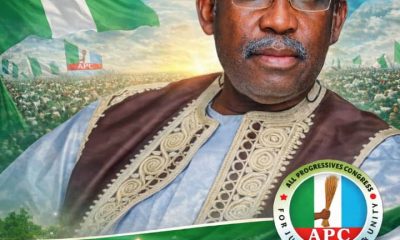

Major General Abdulmalik Bulama Biu (Rtd), mni, Sarkin Yakin Biu, has extended his heartfelt congratulations to the newly elected Ward and Local Government Executives of the All Progressives Congress (APC) following the successful conduct of the party congresses across Borno State.

In a statement he personally issued to mark this significant milestone, General Biu commended the peaceful and well-organized nature of the congresses, highlighting them as a testament to the unity, maturity, and democratic spirit that characterize the APC. He praised the leadership, stakeholders, and dedicated members of the party for their commitment and discipline, which contributed to the smooth and credible outcome of the elections.

Addressing the newly elected executives, Biu emphasized that their victory is not just an honor, but a mandate for greater service, responsibility, and sacrifice. “Our party faithful look up to you to help shape leadership choices that are credible, experienced, and deeply committed to delivering the dividends of democracy to our people,” he stated, urging them to work sincerely and fairly to strengthen the party at the grassroots level.

He called upon the new leaders to promote unity among members and support good governance to ensure the continued progress of Borno State and the nation as a whole.

In closing, Major General Biu assured the new executives of his unwavering support and extended his best wishes for their tenure, wishing everyone a prosperous and blessed Ramadan.

society

UNCOMMON RECOGNITION: Ogun Governor Dapo Abiodun Gifts Car, House to Nigeria’s Best Teacher

UNCOMMON RECOGNITION: Ogun Governor Dapo Abiodun Gifts Car, House to Nigeria’s Best Teacher

By George Omagbemi Sylvester

“State and federal authorities jointly honour Solanke Francis Taiwo in Abeokuta, underscoring the strategic role of teacher motivation and education reform in Nigeria’s human capital development agenda.”

In a move that has sharply refocused national attention on education excellence, Dapo Abiodun has formally rewarded Mr. Solanke Francis Taiwo, a primary school teacher from Ansa-Ur-Deen Main School I, Kemta Lawa, Abeokuta, with a brand-new car and a two-bedroom house following his emergence as Nigeria’s Overall Best Primary School Teacher for the 2025/2026 academic session. The presentation occurred at the Governor’s Office in Oke-Mosan, Abeokuta on 20 February 2026, witnessed by the Commissioner for Education, Science and Technology and senior ministry officials.

Mr. Solanke’s achievement was first nationally recognised earlier this year at the National Teachers’ Summit in Abuja, where he received a ₦50 million cash award for his outstanding dedication and measurable impact in the classroom.

Governor Abiodun clarified that while the bungalow is being provided under the Ogun State Housing Scheme, the car gift was donated by the Federal Government as part of its broader national recognition of exceptional educators. The governor used the occasion not just to celebrate Solanke’s personal excellence, but to showcase what he described as the tangible outcomes of focused policy and sustained investment in education.

Speaking on the reforms driving this achievement, Prof. Abayomi Arigbagbu, the state’s Education Commissioner, tied the success to the Ogun State Education Revitalisation Agenda; a multi-pillar programme that prioritises curriculum enhancement, improved school management, teacher welfare, infrastructure upgrades, digital learning and professional development. “When you implement policies consistently and efficiently, you will continue to record results,” Arigbagbu said, pointing to back-to-back national accolades for Ogun teachers as evidence of meaningful sector transformation.

Experts in education policy have long emphasised the strategic importance of recognition and reward in strengthening teacher motivation and retention. As educational researcher Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond noted, “Sustained improvements in learning outcomes require environments where teachers are both valued and empowered.” While Nigeria grapples with challenges in schooling quality and teacher support, recognitions of this nature symbolise a positive paradigm shift when carefully institutionalised.

Critically, this development also underscores the often-neglected intersection between governance and human capital development; where targeted incentives can elevate the profession’s status and potentially improve learner outcomes. State authorities in Ogun have argued that such incentives are part of a broader ecosystem approach to education reform.

Mr. Solanke, in his remarks, urged fellow educators to view his recognition as a call to persist in uplifting teaching standards. “I promise to continue giving my best to make Ogun State proud,” he said, reflecting a deep professional commitment that goes beyond personal accolades.

In a climate where education systems across Africa seek scalable models of reform, the province’s spotlight on teacher excellence resonates beyond Ogun’s borders, offering a compelling case study of policy, performance and public affirmation converging for societal benefit.

-

celebrity radar - gossips6 months ago

celebrity radar - gossips6 months agoWhy Babangida’s Hilltop Home Became Nigeria’s Political “Mecca”

-

society6 months ago

society6 months agoPower is a Loan, Not a Possession: The Sacred Duty of Planting People

-

society5 months ago

society5 months agoReligion: Africa’s Oldest Weapon of Enslavement and the Forgotten Truth

-

news6 months ago

news6 months agoTHE APPOINTMENT OF WASIU AYINDE BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AS AN AMBASSADOR SOUNDS EMBARRASSING